Four-year-olds Catherine and Alex are playing “bad guys,” taking turns chasing each other around the yard and discussing their plans to “steal the treasure.” Three-year-old Juan Jose is a few feet away, watching and sometimes following the other children when the get too far away. When Teacher Danika asks Juan Jose if he’d like to join them, he tells her that he’s “just watching.” Teacher Danika is a little worried about his hesitance and makes a mental note to see if he joins in play later.

Dramatic play, creative play, parallel play, and more are familiar types of play that are discussed often in regard to young children. Onlooker play is less discussed. It is one of Parten’s stages of play, typically seen in two- to three-year-olds. Sometimes classified as a type of “non-social” play and therefore less discussed than parallel, associative, and cooperative play, onlooker play still has a strong social component. It is one way that young children learn how to engage with others.

Onlooker play doesn’t need to be silent; often onlooking players will talk to or mimic the actions of the people they’re observing. The distinction between onlooker and associative or cooperative play lies in the degree of participation. In onlooker play, children will visually follow and verbally engage but not pick up materials that relate to the game or look like they’re actively playing. In associative play, children will play with the same materials but not sharing ideas. Cooperative play will involve children talking, sharing materials and ideas, and building off of each other’s work.

When is it onlooker play, and when might it be something else?

Like all play, onlooker play is enjoyable. If a child is doing a lot of watching, but doesn’t really seem engaged or expressive, they might not really be participating in onlooker play but instead withdrawing for other reasons. If a child is watching others play and never initiating their own more active play, whether independently or with others, observe more.

Onlooker play behavior usually emerges around 2 1/2, but can happen in older children as well, especially when they are acclimating to a new environment. However, if a child is only engaging to the extent that onlooker play allows for days or weeks, it may be time to look into ways to support that child in entering social play.

How can educators support onlooker play?

The best way is to notice and allow it! Knowing that children may be playing in ways that don’t look like play to adults will help keep perspective that all play is valuable. Making space for onlooker play might mean doing less, not more.

Teacher Danika in the example above could be sure Juan Jose has plenty of space to watch Catherine and Alex, as well as opportunities to recreate their ideas on his own to process what he saw.

Find Part 1 HERE

In early childhood spaces, there is much research on the field of attunement, regulation and co-regulation. When an adult is able to regulate their own nervous system, they can help little ones calm their minds and bodies, and create an experience where children can be aware of their own emotions, listen and learn from them, and choose from an array of strategies to move from dysregulation to a regulated state. Some say that a dysregulated adult simply cannot help to regulate a child.

I am continually impressed with the array of strategies I see in elementary schoolers for being able to move from an overwhelming feeling into a place of more equilibrium. To be able to have feelings and body awareness, to then find language to describe that feeling, choose some preferred strategies, then later reflect on why and how they feel the way they do. This allows them to better cope with the natural ups and downs of the day and the body’s various states. This is a far from easy or clean process with linear outcomes, but it is an important process. I am still learning so much about my own regulation system (while simultaneously trying to be a leader for my children and students as I work to rewire and reframe my own responses!)

When kids are in environments with teachers modeling rich language around feelings, behaviors and choices, normalizing emotions, they will develop more social and emotional knowledge than without. It moves us away from how so many were raised to believe that certain feelings are acceptable, while others are not. To truncate, to push down, to punish ourselves and others for having completely acceptable, human emotions.

Many times, children are leading us.

I can’t imagine another environment so ripe as to support the development of attuned leaders. Amazing brains, full of potential, growing, learning, and developing their spindle cells and oscillators to connect with others? As those working with children, we are truly building the brain-leaders for tomorrow’s world. In our digital age, it is more crucial than ever that we show little ones how to read faces and bodies, hear tones in voice, scan and encode humans. And know that someone is deeply attuned to them. To their magic.

We now know conclusively that we are creating future leaders who can positively impact others.

So, as Brene Brown speaks to boardrooms and with C-Suite executives about the importance of having an emotional landscape, we know that within the interactions at our sensory tables and our play areas, our centers and stations and playgrounds and parks, this is where leadership begins.

Brain-based, connected and attuned, empathetic leadership.

There is much information about the importance of teaching empathy and having a feelings-aware environment in early childhood spaces. It is simply good for children; good for relationships; good for growth; and good for the adults that are supporting and guiding the learning.

As Brene Brown shares in her book Atlas of the Heart: Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience:

“Our connection with others can only be as deep as our connection with ourselves. If I don’t know and understand who I am and what I need, want, and believe, I can’t share myself with you.”

What Brown does here is both uncover and shine light on the importance of having access to our feelings so that we can share, and so that we can communicate with ourselves and take that knowledge and those feeling words and bring them out into the world. In general, we lack the depth of words to accurately describe our feelings. This essentially limits how we can share ourselves and connect to others with depth and deeper understanding. Until recently, and because of research and work like Brown’s, we may not have known how stifled we actually are. That we have mostly been living in a feelings-shallow environment. But now we know. And we can do better.

Now let’s move into a different, yet related field of study—that of Mirror Neurons. Spindle Cells. Oscillators. The parts of the brain that fire up when we are in social situations, when we are interacting with other humans.

According to a 2019 Harvard Business Review article “Social Intelligence and the Biology of Leadership” by Daniel Goleman and Richard Boyatzis, studies of the brain show that leaders can improve group performance by understanding the biology of empathy (the ability to understand and share the thoughts and feelings of another person.)

Goldman and Boyatzis have been studying the brain within a particular field called social neuroscience. It is the field of study that examines what happensinside the brain while people interact.

And it shows us interesting truths about something rather unexpected. About what makes a strong leader.

This is where mirror neurons come into play. Mirror neurons fire up when we consciously or unconsciously detect someone else’s emotions through their actions. And according to how the brain works, “collectively these neurons create an instant sense of a shared experience.”

And this is also where spindle cells enter the scene. Spindle cells are responsible for sending information about how we feel about a person. Spindle cells are four times the size of other brain cells and have an extra long branch to quickly transmute thoughts and feelings. Our emotions, beliefs and judgments form to create our social guidance system.

The real gem here is that certain things that leaders do, specifically exhibiting empathy and becoming attuned to others’ moods “literally affect both their own (the leader’s) brain chemistry… and that of their followers.” This means that both leaders and employees’ brains can mimic and mirror each other, forming a sort-of symbiotic space. There are some hard metrics that demonstrate that when a leader is able to attune and attend to the needs of their group, they have the power to influence their team’s (and their own brain pathways in powerful, and now measurable, ways. With the now established ways of being able to scientifically measure human development, we are able to capture how these skills of empathy and human understanding can transfer to effective, compassionate leadership.

Empathy can be practiced, so it makes new pathways in the brain. This makes stronger, more attuned, more positively influential leaders and teams.

While fascinating, you may be wondering what this has to do with our youngest learners. Or even education for that matter. While Brown and Goldman and Boyatzisand’s work isn’t related specifically to the field of early childhood, it isn’t a drastic leap to consider that the caretakers of children are those very leaders as well. Let’s combine the ideas we just read about- take what we now know about the inner workings of the brain, how humans interact with each other, and how effective leadership can form and commit to stating that these ideas are immensely important for the field of early childhood.

Because those who work with children and their families lead and interact with children everyday. We are the leaders of children. Leaders of families.

Find Part 2 HERE

When a family makes a commitment to a child care program, they’ve made a statement that they trust the provider to keep their child safe and healthy, and provide an educational and loving environment for that child to grow in. This can be the first step to a strong and long-lasting relationship when educators take the time to intentionally build that with the families of children in their care.

Why is it beneficial to build relationships between educators and families? Often, child care educators are a family’s first experience with having an unrelated adult care for their child. As the introduction to extrafamilial care, child care providers set the tone for the way families engage with all of their child’s education. Setting the stage with warm and caring professional relationships will support families engaging with all of the systems that they will participate in with their child.

A strong relationship between family and child care provider also directly and immediately benefits the child. Family child care educators and families are the people who spend the most time with a child and are in the best position to advocate for them and support their growth and development. When families and educators build strong relationships together, they can communicate more effectively when concerns or disagreements arise. Maintaining relationships with families offers educators the opportunity to better understand every child, and it can give families the comfort necessary to participate in the child’s program and share the interests and skills with the educator and children.

How do family childcare educators seize this opportunity to connect with families and build those professional relationships?

- Start before day one: Although families already have plenty of paperwork to do to enroll, some educators add a “getting to know you” page where families can answer questions that will support the provider in understanding their families history, preferences, and needs. Some sample questions include:

- What language(s) does your child hear and speak at home?

- Who lives in your child’s home(s), including pets? Who do they visit with frequently?

- What do you like to do as a family?

- What does your child typically choose to play with?

- Tell a story: The days can get busy, but proactively making note of something the child said or enjoyed during the day to communicate with families at departure time will maintain that relationship. Prioritizing face to face communication, even for you a minute or two at a time, will make bigger conversations easier when they become necessary. This doesn’t have to happen every day for every child, but the first few days a child is in a program are extra important for making this connection.

- Invite them in: When children are interested in a subject that a parent knows about, or the opportunity for a field trip arises, inviting families in either individually or as a group to share their experience or supervise a trip will build bonds and memories.

For Reflection:

What one action can I add to my day that will help build those reciprocal relationships with families?

This printable checklist will help educators examine their routines and what is or isn’t working for all of the children. Use this to help track down why some parts of the day are consistently challenging, or problem solve for behaviors that challenge educators.

Sometimes, if we take a moment to pause and look around (yes, it is hard to do!)…we can really see what is around us. We may realize that many of the answers to questions we ask are already there for us, just waiting to be discovered.

As early childhood educators and professionals, this pause may be through the process of asking a question in a new way, looking for a different outcome, truly seeing with new understanding. Or it may be a stepping stone for something we already know, but takes us into an unexplored direction.

As early childhood educators and professionals, this pause may be through the process of asking a question in a new way, looking for a different outcome, truly seeing with new understanding. Or it may be a stepping stone for something we already know, but takes us into an unexplored direction.

The journey of outdoor learning is like that.

For those that are already on this path, you know. For those curious and wanting to learn more, I invite you to read on.

Every outdoor environment has something to offer. Something to discover. Something new that can enrich our lives. It can transform the way in which children interact with the world. Our world. Their world.

The research is abundant and clear regarding the many benefits of children’s outdoor learning and nature play.

So, whether you have extensive or minimal outdoor time at your center, whether you have a forested area, a field, an open lot, or a small space or even just a few trees in which to explore, nature learning CAN happen. But, I stress that it be explored with that curious mindset. If you are thinking of all of the barriers that may stop you from implementing outdoor experiences for your children, you are not alone. But this is so new, so different! I have so much built into what I already know and do! This is too much work! Change IS hard, but as you read on for practical tools and ideas to integrate more nature into your day, you will find it is not only doable, but full of unexpected gifts. Getting Started Teaching Outside from Get toGreen through Fairfax County schools provides straightforward tips.

So, whether you have extensive or minimal outdoor time at your center, whether you have a forested area, a field, an open lot, or a small space or even just a few trees in which to explore, nature learning CAN happen. But, I stress that it be explored with that curious mindset. If you are thinking of all of the barriers that may stop you from implementing outdoor experiences for your children, you are not alone. But this is so new, so different! I have so much built into what I already know and do! This is too much work! Change IS hard, but as you read on for practical tools and ideas to integrate more nature into your day, you will find it is not only doable, but full of unexpected gifts. Getting Started Teaching Outside from Get toGreen through Fairfax County schools provides straightforward tips.

The North American Association for Environmental Education (naaee) offers three categories to plan for and organize outdoor learning experiences; TEACHING, SAFETY and the ENVIRONMENT.

When we are spending time outside with children, we can learn from both the space and the place. Learning outdoors (simply being outside!) is also a stand-alone benefit to whole-child development…simply being outside is good for children and schools.

- What do I teach?Natural Start: The Teaching and Tinkergarten: Tinkergarten outdoor learning ideas

- It seems so risky! Natural Start: The Safety

- Where? Natural Start: The Environment

Practical tips for clothing and snack time:

Sometimes starting small is best. A new nature walk routine with prompts such as “Tell me more about what you notice” and “Can you say more about that?” Or integrating a math focus such as “Nature explorers, today we are going to notice the nature around us in groups of three” may be one of the most important changes you make this year.

Sometimes re-thinking a routine typically done indoors and/or on a screen and bringing it outside, is best. Read-alouds, journaling, and songs may now take place on foam sit-upons or a tarp. Some extra minutes teaching and practicing outdoor learning routines are well worth the time.

Sometimes planning with your teaching team and doing your own adult nature-scavenger hunts, and surveying the areas for safe and creative play, is what is best.

Nature is joyful. Nature is powerful. Nature is an incredible teacher. I invite you to take the small steps or giant leaps needed in order to provide critically important outdoor experiences for our children. Working as a teacher and coach in countless spaces and places for over twenty years, I can truly say that what nature as a teacher gifts to us, is incomparable.

So, slow down, look around, and ask those questions that nature has been waiting for us to ask.

“If we truly want to make nature-based education meaningful and accessible for all children and families, we must strive to approach education in the context of not just the class, or the forest, but the place, this entire remarkable world of which we are all a part.” – Kit Harrington

“If we truly want to make nature-based education meaningful and accessible for all children and families, we must strive to approach education in the context of not just the class, or the forest, but the place, this entire remarkable world of which we are all a part.” – Kit Harrington

This printable tip sheet for transition times offers educators some practical strategies for helping children transition between activities, or from home to school.

It’s likely that you have already or will someday work with a family whose children are learning more than one language. There are a number of approaches that families may take to achieve this, including implementing only one language at home and another in the community, or using the One Parent, One Language approach which is just what it sounds like: one parent speaks one language to the child(ren), while the other speaks a different language.

Why do multi language learners benefit from an approach that supports all of their languages?

Not too long ago, the prevailing belief was that children should learn English as soon as possible and focus only on English. Many people thought that learning more than one language was confusing and would lead to language impairments. Now we know that children who learn more than one language are not at any higher risk of speech or language issues, and when assessed appropriately tend to have larger total vocabularies than monolingual children. One way to support multi language learners is simply to make sure their families know how beneficial it is to keep their home language!

There are also significant social-emotional benefits to uplifting a child’s home language. Even very young children can learn early on to “hide” a part of their identity when they don’t feel a social approval for it, such as by no longer speaking in their home language, even with family. When a child feels that their home language is valued, it helps to maintain a sense of pride and “being seen” that supports children’s identities as learners, members of the national culture, and members of their home culture.

How can educators support children’s development in a language they don’t know?

To support children’s multicultural identities, sharing bilingual books, or books that feature some words in a child’s home language, are a great way to demonstrate support for the many ways we have to communicate and introduce all children to the language. Some children might want to be the expert in their home language and have the chance to correct a provider or peer’s pronunciation, and some may not want the attention that brings. Even if you can’t find books with vocabulary that isn’t in English, you may find fairy tales or stories that incorporate cultural features that are familiar to those children. Partner with families for suggestions or ask your local children’s librarian to help you locate appropriate materials.

What are some practical tips for working with children and families when there is a language barrier?

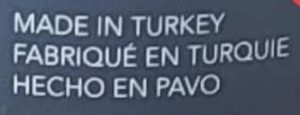

When a family doesn’t speak English, and a provider doesn’t speak the family’s home language, there are some tools to build relationships. While they aren’t perfect, there are many technological ways to facilitate communication across languages. The free Google Translate phone app offers the ability to translate conversations in real time across dozens of languages, with the option to write and translate if spoken word isn’t supported in the language you need. The website can also translate newsletters or other written communication. Just be aware that computers make mistakes that real people do not, like this label on a beauty product that was made in Turkey, the country– except, in Spanish, it appears that it was made in a turkey, the bird!

Image via Steve the vagabond and silly linguist 🇿🇦 on X: “Made in a turkey https://t.co/uAGet2vMKg” / X

Image via Steve the vagabond and silly linguist 🇿🇦 on X: “Made in a turkey https://t.co/uAGet2vMKg” / X

Learning some words in the child’s home language is important– particularly words relating to their needs, like “hungry,” “tired,” and “toilet” or “diaper.” Making yourself a phonetic “cheat sheet” can help. For example, if a child who speaks Japanese joins your group, you could write:

Hungry= on-ah-ka-ga-su-ita

Tired= tska-re-ta

Toilet= ben-jo

Diaper= Oh-muh-tsu

If possible, ask the family to teach the proper vocabulary and pronunciation– it’s possible the family uses a local accent or dialect that’s different than what a translator uses as standard.

How can educators support peer relationships across languages?

There are many kinds of play that don’t require a lot of language at first! Offering art and sensory experiences with enough materials to share will naturally lead to children demonstrating their discoveries to each other. Large motor play, like obstacle courses, will be easy for children to model for each other.

Educators can actively encourage children to include each other by inviting the new child into activities or asking one child to be the new child’s “partner” and show them around.

Remember to model empathy for the new child. Entering a new environment can be frightening for many children, and not understanding the language adds an additional dimension to contend with. Talking with the children in advance about how to help their new friend feel more comfortable might lead to some great ideas that wouldn’t be obvious for adults. This can also enhance peer relationships to offer children the opportunity to learn what is comforting for each member of the group.

Questions for Reflection:

- Which of these strategies seems like it would be the easiest to incorporate into your program?

- What other ideas do you have to support multi language learners and their families?

During times of political upheaval and increased violence, our obligation to be informed citizens can feel at odds with our obligation to protect the children in our care. It’s difficult to maintain the best practices of avoiding the presence of television/radio/podcasts when there is so much information that feels critical to take in. Add to that comments from families and children, and it can feel like there’s nothing else to focus on.

Our work is not apolitical. Decisions about funding, licensing requirements, and more decisions that apply to child care are made at the state level and are becoming federal questions as well. Our work is political, but our responsibility to children defies party lines or beliefs and must focus on their needs.

How can a provider respond appropriately to children’s questions and concerns? What do young children need when the news is frightening and adults are responding strongly?

Root your responses in reassurance: the children need to know they are safe, and you and their families will keep them safe.

Hearing about real-world violence is scary; young children will naturally feel unsafe, even if they are very removed from the situation.

When older children really want to talk out what they’ve heard, this includes emotional/ideological safety. It’s very likely that children and families have a range of opinions that will be expressed many different ways. Maintaining emotional and ideological safety allows for different viewpoints and centers the idea that while there may be many different interpretations of events, the safety of each individual will not be compromised by expression of associated hate speech.

Avoid showing photos or videos of the events or listening to or viewing media where they’re being depicted and discussed.

Even when children are interested and want to talk about what they’ve heard, it can be overwhelming and frightening for children to view depictions of violence. As we know, children are always listening. Save your own information for after hours.

Find a way to move on from the conversation productively.

Children (and adults!) can get overwhelmed easily by ruminating on events outside of their control. Allow children to play out their experiences and talk as they need to but be prepared to interrupt advantageously when you see signs that it’s getting overwhelming. Bring their focus back to how they can feel safe and help others feel safe, and what they need to participate in community effectively. Preschoolers need the empowerment that comes from being a helper; how can they help in your space?

Redirecting early on can reinforce to children the idea that the world is frightening, and even adults are uncomfortable with the topic at hand. Being a sounding board and then helping the children move on sends the message that they are heard, and the adults can keep them safe.

Be prepared for play to emerge from current events.

Young children process the world through play, which can be challenging when they’re hearing and seeing violence. Know that processing through play is healthy, even when it involves themes that adults would prefer to avoid. Observe closely. Notice when play is becoming disruptive to other children and prepare to step in if that happens to offer a break to the affected children.

For more resources on talking about current events with children, see:

Discussing Race, Racism and Police Violence | Learning for Justice

Talking with Students About Shocking or Disturbing News | Common Sense Education

How to talk to kids about scary news : NPR

Gun Violence and Children: Practical Ways to Provide Mental Health Support, Part One

One of the joys of family child care is the length of time providers can spend with the children in their care, and the growth that happens in those years. This also means that providers need to remain adaptable, and ready to change their program alongside the children. Communicating with families at enrollment and checking in regularly about when and how long children are sleeping, how often they’re eating, and their state when they get home (overtired? awake until 11?) can help inform routines as children grow.

Of course, in mixed age groups, it’s very likely that there will be children who have seemingly conflicting needs at the same time. How can one provider offer an active preschooler adequate time outdoors, while also feeding infants as they get hungry, and attend to toileting and diapering needs as the pop up?

There are three things to keep in mind to balance it all (most days!):

- Preparation: Communicating with families about young children’s needs, as well as using the provider’s own observations, should inform the construction of the routine. Not only should each child be considered as an individual, but the group as a whole serves as another perspective to consider. Every time the group composition changes, there’s a good chance some part of the routine will as well.

- Equipment: Ideally, there should be spaces indoors and out for both active and quiet play; resting; and eating. Of course, space can be at a premium in any child care setting, so adaptability is key. Can a waterproof box with diapers, wipes, diaper table paper, soap and paper towels live near your garden hose?

- Flexibility: don’t let the clock stress you out– it’s a reference point, not your boss. If the children are contentedly playing, don’t let the clock tell you or them that it’s time to stop! Conversely, if some are clearly tired and hungry, feel free to move lunch and rest time accordingly. While many states have regulations that require infants to be fed and given naps on a highly individualized schedule, it’s okay to let a tired child rest or a hungry child have a cup of milk or other snack outside of scheduled meal times.

For Reflection:

What times of day are the most challenging to meet everyone’s needs?

What would support you in partnering with families around children’s need for routine?