As part of our social emotional learning curriculum, we read a story about a different social-emotional concept using sight, touch, and sound to engage children and solidify the skill-building process.

I always incorporate a stuffed animal that correlates to a different social or emotional need. For example, unicorns for creativity, bears for feeling love, sloths slowing down, snail feeling brave. My goal is to tell a story or read a book I find about that SEL goal and pass the stuffed animal around and help them believe in themselves and their abilities. To remind them we can get through hard times, and we don’t have to do it alone.

Daily we work on positive affirmations and the idea that their opinions about themselves matter. We’ve also talked about how to handle difficult situations and when to ask for help. Being a teacher, I’m doing everything in my power to help guide, kind, empathetic, and strong kids.

Social Emotional Learning is instilling feelings of self-worth into our kids. We use affirmations in response to many situations, like conflict-resolution needs, self-esteem needs, and emotional regulation needs to name a few. And using affirmations daily I notice the kids pulling out these types of positive sayings on their own, without my initiation.

The specific skills the children are learning include:

- Interaction — physical touch, eye contact, and playfulness

- Connection — reading positive affirmations and having them repeat them to you (if possible)

- Reflection — practicing the learned concepts and skills

As teachers we honor the emotional lives of children and enable them to find the words to express themselves as they come to terms with their complex feelings.

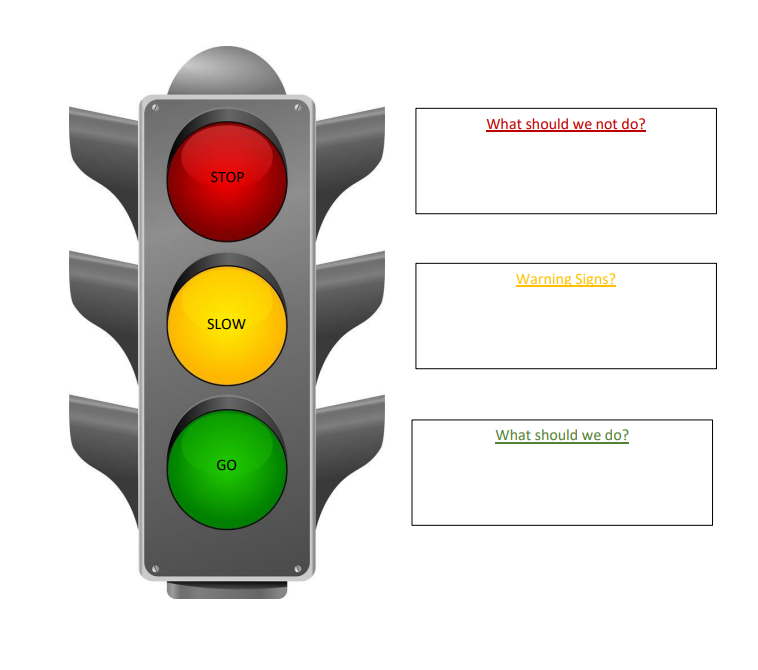

From Megan K. Lerner and Anthony T. Vesco’s presentation on Strategies for Managing Stress and Trauma-Related Distress in Preschoolers, the Stoplight can be completed with individual children or as a group to teach self-regulation skills, as seen in the presentation here (start at 52:00):

One of the most perplexing things that can happen when a child’s inappropriate behavior is being addressed is laughter. We’re prepared for averted eyes or signs of shame, but why is laughter some children’s go-to?

Do they believe their actions are funny? Do they think the adult is being funny? Is it an act of rebellion or disrespect?

Actually, none of the above. Laughter is a stress response. While it’s a difficult perspective shift to make, seeing the laughter and interpreting it as crying is likely much closer to the child’s internal state than most people would assume.

Knowing this, what can we as providers change in response to a child’s laughter and perceived defiance? How can we make our own mental shift to handle this effectively, still teach the child the prosocial skills we are looking to impart, and not cause harm by becoming more intense and escalating the child’s sense of fear?

The first step is deescalating yourself to be ready to coregulate. This might be a mantra, counting backwards, or slow and purposeful breathing to remind yourself that the child is struggling.

Next is coregulation: helping the child to feel safe again. This can be hard if you’re still focused on the initial behavior. Rest assured, this doesn’t mean not addressing the initial incident. It does mean that the child will be emotionally prepared and ready to learn from it. Breathing with the child– one of my favorite methods is five-finger breathing, as shown in this video:

Once you’re both feeling calm, then it’s time to address the initial challenging behavior.

Questions for Reflection:

Have I seen children laugh or otherwise respond in an unexpected way to correction? What have I done before?

What might get in the way of taking the time to calm down myself and the child?

When else might it be useful to implement intentional calming strategies like finger breathing with children?

What can a child learn from a fight? A lot, with the right opportunities.

A dispute with a peer can teach a child about how to voice their own needs, how to weigh the needs of another, and how to compromise and problem-solve with others.

In the Japanese practice of Mimamoru (literally, “watch and protect”), early childhood practitioners are trained to intervene minimally and later than many American early childhood educators would expect, while still closely observing children’s fights. The principle behind this is that while the adult’s role is to protect the children, children need the experience of navigating social complexity to build their social skills. A child who hits another and is then sent away from the activity learns that the adult nearby doesn’t want them to hit but does not learn how to get their needs met. When that same adult stop in, checks on the child who was hit, and helps both children verbalize their wants and needs, both children have the opportunity to understand each other and find a solution.

Perhaps the more difficult situation here is one where the attacks aren’t physical, but emotional. Relational aggression (e.g. “You’re not my friend!” or “You can’t come to my birthday party!”) can be more difficult to intervene in, and harder to spot. This also tends to peak in late preschool and early elementary years as children refine their definition of friendships and understand what it means to be a friend, as well as the power that comes from being included or excluding others.

In either act of aggression, how can the educator offer a learning opportunity instead of simply managing or shutting down the behavior? People are born with the desire to connect, and emotional resilience, as well as a guiding moral voice. What needs to be scaffolded are the skills to advocate for oneself and listen to and hypothesize about others’ perspectives.

First, look at the purpose of adult interventions: no one wants the children to be hurt, physically or emotionally. But in the same way that learning to walk comes with a few tumbles, learning to be a friend and participant in a community comes with its own missteps. If children cannot learn from each other and us when they’re small, they won’t have the experience to navigate social relationships as they become more complex.

This is the platform on which larger concepts of restorative justice are built; instead of punishing the person who harmed another, we work to ensure that the person who was hurt is comforted, and the person who did the hurting has the resources to avoid doing it again.

Questions for your reflection:

- What was your first reaction when you thought about waiting to intervene?

- What are your current intervention strategies when children are fighting?

- How could you integrate a “pause” before intervening?

- What else could you do to support children in learning conflict mediation?

The progression every person undergoes to understand themselves and others. While social emotional development, like other development, happens in a predictable sequence, adults and peers play a significant role in teaching children appropriate ways to socialize and handle their emotions. The foundation of this development is coregulation, when a distressed child is met by a caring adult who helps them to reregulate and teaches them the skills needed to self-regulate.

Social-emotional learning can be one of the most misunderstood by adults– we see a child who is “aggressive” or “mean” or “a hitter,” and correcting the behavior is second nature, but finding ways for the child to meet their underlying need in a way that doesn’t harm others is much more difficult.

This webinar discusses how providers can work to support all children in becoming empathetic community members.

Consider: How do the principles of safety needs and growing needs influence how you plan your program? How can you prioritize building secure attachment with the children in your program?

This nine-part course (approximately 3 hours and 45 minutes) from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network will teach participants about “early childhood social-emotional development; the impact of stress and trauma; reflect on the possible meanings of children’s behaviors; explore the influence of culture on families’ socialization goals; and become familiar with a number of strategies aimed to promote secure attachment and safe socialization practices.”

Providers will need to sign up for a free account to access this resource.

Calming spaces in early childhood environments are widespread but creating them with intentionality and teaching children how to use them can be big tasks. When we see disruptive behavior as a sign of a dysregulated child, and provide the tools for that child to re-regulate, we are setting them up for lifelong success as they grow to become people with strong self-regulation and impulse control skills.

These two handouts provide opportunities for you to reflect on how adults use their sensory systems to self-regulate and how to use that information to create calming spaces to support children’s social-emotional development.

This printable/downloadable resource will help providers understand difficult behaviors that may be a result of trauma, and support children in developing skills to overcome their difficulties.

TS Strategies for Helping Youth With Trauma Exposure

Accessible version below:

Strategies for Helping Youth with Trauma Exposure

Strategies Emotional Dysregulation

Assist them in identifying their emotions

Using feelings charts/emojis, asking them to rate their intensity

Use words to describe how you (the adult) are feeling and use that to model expected behaviors for the child

Allow them to express their own thoughts

“What is your brain saying to you?”

Incorporate superheroes or cartoon characters to assist with talking back to thoughts and/or feelings

Have a designated coping space

Fidgets, bean bag chairs, pillows/stuffies, lowered lights, minimal noises, tents

Provide clear and concise directions

“We need to sit down.”

“Let’s take some deep breaths.”

Consider the basic need of the child to help improve their mood

Do they need a snack, nap or water

Strategies for Withdrawal

Allow them to take space for a while and see if they naturally engage with time

Identifying specific, labeled positives in the child, even then the child is expressing feelings of guilt, anger or sadness

Validate the feelings by saying things like, “I bet that is really scary!” or “That would make me mad too.”

Encourage them to engage in a positive activity that increases energy and is the opposite of their urge to isolate/shut down

Examples include having a dance party, making them a special helper, let them choose an activity for the whole group to engage in

Give them choices to take breaks or to do independent activities while also encouraging them to join the group (don’t give up!)

Remind the child that when they are ready to participate everyone will be excited to join them

Assist them with joining in a task with a partner/small group

Scaffold interaction until you can fade yourself out

Strategies for Aggressive Behaviors

As long as they have safe hands and feet, let the child know you will be ignoring the outburst and then immediately provide praise for calm body behaviors when you see them

Keep language focused on their behavioral choices and not focused on the child’s personality or characteristics

Try saying, “I see your hands are having a hard time being safe.” And not: “You are usually such a safe person, what is happening here?”

Consider the purpose of the child’s behavior

Are they trying to escape a situation

To get a tangible need met

To gain attention of an adult or test the attachment of the adult

To self-stimulate (due to an under-stimulated or “numb” nervous system)

Understanding the purpose of the behavior can assist you in meeting the child’s needs and provides context for negotiating your next step

Ask Yourself These Questions Before You Intervene

Can I shift my perspective from one of managing behaviors to supporting and growing a child’s executive functioning?

Can I view problematic behaviors as a child not having mastery over certain executive functioning skills?

Am I optimizing children’s sense of autonomy and providing an opportunity to learn and problem-solve?

Young children are absorbing information from everything around them, but they haven’t yet developed a “filter” through which to assess that information, which is part of why it’s so important to discuss the media they are taking in with them directly.

I hope to introduce you to both specific books with excellent opportunities for conversation with young children, and also some jumping off points to carry into your discussions about books and other media as you consume it with the children in your care.

To start off, a classic: The Little Mouse, The Red Ripe Strawberry, and The Big Hungry Bear.

This is one of my favorite books to consciously introduce young children to the amount of information they can get from facial expressions and body language. Before reading it to the children, flip through and notice the huge variety of emotions that are readily apparent on the Little Mouse’s face. Pride, surprise, fear, regret, anxiety, confidence, and joy all stand out to me on different pages.

As you read, pause to notice out loud how the mouse appears to be feeling. Mimic the expression on your own face and see if the children do it as well. With older children, you can “wonder out loud” with statements like “I wonder what the mouse thinks the bear will do?” or “I wonder what he’s planning,” or invite discussion with prompts such as “I think he looks scared, here; look at his eyebrows. Do you see anything else that might tell me he’s scared?”

Using books to teach social-emotional competence gives children a low-stakes time to practice reading others’ emotions. When children haven’t had the opportunity to practice “reading” others’ faces, they have to learn on the fly, which can mean more conflict and more social struggles. For example, a three-year-old might not notice that the friend he’s chasing in a game of tag isn’t having fun anymore until that friend is in tears, rather than seeing his friend’s facial expression and other non-verbal cues and stopping the game.

Learning to read body language and facial expressions takes time and comes more easily to some children than others. When we take the time to consciously teach children about it, we can help build their empathic skills as they learn more about other people.