Within the Reggio Emilia approach, and now in many early childhood programs, the environment where children spend their time is typically called the third teacher. The environment helps determines the flow of the day, what children learn and how they interact with one another. Having the right amount, variety, and types of materials in an early childhood classroom will make the day run more smoothly and will be more engaging for the children, thus in turn will make it easier for the teacher.

Knowing the why, when, and how to rotate toys is important and a worthwhile task, based upon information gathered through child observations. Through observations of the children in care, we can determine if, when, and what types of materials need to be rotated in the environment. The provider knows the children in their care very well and soon can see patterns emerge that will help the provider make specific adjustments in the environment.

Let’s consider some of the reasons why we rotate toys in a childcare environment.

A child may have mastered a certain skill and by changing specific materials in the classroom we can help scaffold the child to the next skill level. Children learn through facing appropriate challenges, but it’s important to make the challenge achievable. We don’t want the child to feel frustrated or lose interest. A skilled teacher is able to observe students and notice these small changes and find materials that will spark curiosity and interest. We may want to teach a new skill. Placing new toys and materials in the classroom can help a child learn a new skill, such as sequencing, stacking, or balancing. We may also want to challenge that skill and make it slightly more difficult by adding something new to use. Safety is top priority so make sure that items placed in the environment are safe for all ages of the children in the classroom. This can be challenging in multi age programs but can be overcome with a little planning and thought. A child’s individual interests will also play a part in the items we choose. We know that children will play with things that interest them. Having materials of interest will mean the children will explore and play with things that interest them and that are relatable and familiar to them. Common household items that children are familiar with are good to add when possible.

Now let’s take a look at when we might remove certain materials from the classroom environment. When children have lost interest, aren’t playing with as intended or are mistreating the materials, this is a good time to remove them and find materials that the children are interested in. Intended uses of toys and materials may vary from item to item. I believe that a toy does not necessarily have to be used exclusively for its intended purpose. I believe children should be able to use their imagination and creativity and use items in different ways, not just the way intended from the manufacturer. Items that are distracting and stress inducing should be removed. Some children are more sensitive to certain colors, sounds, and even how much is available in the environment for the children at one time. Remember less is more.

Finally, how we display items in the environment helps convey to the children what is expected of them and where items belong. Neatly placing items on a shelf helps children put things away on their own. Labeling shelves and baskets make clean up a breeze. They can also see and reach what they would like to play with, and this allows for independence. Placing similar items together on the shelf in an aesthetically pleasing way, where children can see them shows we care about our materials and toys, and they deserve a place in the space. Don’t over crowd the environment. Less really is more in childcare. If too many choices are available to children, they don’t play well with any of them. Choose items that interest the children and things they are familiar with and see in their day to day lives. We want these items to be relatable to children and familiar. Children want to use “real” things they see in their everyday lives. If teaching a theme, we may want to choose items that relate to the theme being taught or based upon the current season. Rotating 1-2 things a week and making adjustments as needed is less stressful on children than changing everything at one time.

Creating an organized and inviting environment is not difficult. With a little planning and time, you can create a relaxing and organized childcare space to enjoy for children and teachers alike.

Early Childhood Education can have a lot of buzzwords and misunderstandings. This “Philosophy Spotlight” series intends to introduce you to the origins of a number of currently used philosophies directly from the writings of their founders and accomplished practitioners, as well as modern practices and ideas associated with these philosophies. Note that many of the philosophies and philosophers we reference in the US are Euro-centric in origin. I will do my best to integrate philosophies of development and learning from a more diverse body of knowledge, for the benefit of all children and providers. You’ll notice a significant amount of overlap between philosophies, as well as some stark differences. Use these articles to consider your own approach to early education, and maybe refine how you see you work and design your program. These are intended to be broad overviews; please see the references if you’d like to learn more about each one!

Origins: After Italy had been destroyed as a fascist power during World War II, there was a movement to rebuild the country in a way that would support its citizens in pursuit of freedom from oppression. The first Reggio Emilia school was built by families seeking to create a new school for their children as they rebuilt their community. They quickly grew into a network of preschools and infant toddler centers through the 1960s and 70s. In 1991, Newsweek called the Diana school, one of Reggio Emilia’s preschools, one of the best schools in the world.

Modern Regulating Bodies/Standards: The term “Reggio Emilia Approach” is trademarked, leading to many programs describing their philosophy as “Reggio Inspired”, although there is no regulating body outside of Italy that controls the use of the term. A school cannot be certified as a Reggio Emilia school, nor can a teacher be a certified Reggio Emilia teacher. There are organizations in the International Network that further the spread of information about the Reggio Emilia approach, but do not serve as regulators.

Theories and Theorists:

Loris Malaguzzi is considered the founder of the Reggio Emilia approach. He was a psychologist trained in pedagogy and had previously co-founded a school for children with disabilities and learning difficulties. While working there, he was approached to collaborate with the new network of preschools and infant-toddler centers.

Values:

Children are active protagonists in their growing processes: Every child can and has the right to create their own experiences as an individual and member of a larger group.

Progettazione/Designing: Education is shaped by the design of environments, participation, and the design of learning situations. It does not happen to the same degree in predesigned programs or curricula that are premade.

The hundred languages: The Hundred Languages of Children are a metaphor for the potential of children and their thinking and creative processes. It is a central value to honor all of children’s forms of self-expression equally.

No way. The hundred is there: A Poem by Loris Malaguzzi (translated by Lella Gandini)

No way. The hundred is there.

The child

is made of one hundred.

The child has

a hundred languages

a hundred hands

a hundred thoughts

a hundred ways of thinking

of playing, of speaking.A hundred always a hundred

ways of listening

of marveling, of loving

a hundred joys

for singing and understanding

a hundred worlds

to discover

a hundred worlds

to invent

a hundred worlds

to dream.The child has

a hundred languages

(and a hundred hundred hundred more)

but they steal ninety-nine.

The school and the culture

separate the head from the body.

They tell the child:

to think without hands

to do without head

to listen and not to speak

to understand without joy

to love and to marvel

only at Easter and at Christmas.They tell the child:

to discover the world already there

and of the hundred

they steal ninety-nine.They tell the child:

that work and play

reality and fantasy

science and imagination

sky and earth

reason and dream

are things

that do not belong together.And thus they tell the child

that the hundred is not there.

The child says:

No way. The hundred is there.

Participation: Children are welcomed to participate in relationships, in the classroom and community. This is to give children the “feeling of solidarity, responsibility, and inclusion, and produce changes and new cultures” (Reggio Children).

Learning as a process of construction, subjective and in groups: Every child constructs their own knowledge, through conversation, research, and discussion.

Educational research: Adults interacting with children should see themselves as researchers and use their documentation as research into children, groups of children, and learning. Educators should be encouraged to continue constructing and reconstructing their knowledge and practices.

Educational documentation: Adults and children take videos, photos, and work samples to document the learning the children are engaging in. These documents are used to provoke discussion and through between educators, between children, and between educators and children together.

Organization: Time, space, and work are all organized to reflect the values of the school and projects.

Environment and spaces: Interior and exterior spaces are all designed and organized to interact with the people in the space, shape learning experiences, and inspire thought and creativity. Care of the environment is critical, and maintaining the aesthetics of the space is intended to create pleasure and joy in the people who use the space.

Formation/Professional growth: Professional growth is the right of individual educators and the whole group. In Reggio Emilia, professional development is part of educators’ working time, and occurs within staff meetings and the larger city, national, and international context.

Evaluation: The schools should be evaluated frequently by their coordinators, educators, community members, and families to ensure that they are meeting the needs of the children and families.

What You Might Observe in a Reggio Inspired Program:

Many Reggio Emilia inspired programs place a heavy emphasis on the arts, particularly visual representations and planning, along with guided exploration of visual arts materials. There will likely be documentation of children’s work hanging up for children and adults. Oftentimes, children in Reggio Inspired programs use more “loose parts” than traditional toys. As part of the Reggio value of designing, children are offered “provocations” which are curated sets of materials designed for children to explore and experiment with to provoke their thinking and extend their interests. Provocations can look like a tray with small balls and ramps; unwrapped crayons, leaves, and thin paper for printmaking; boxes, tape, and crayons to create with; or anything else that children might use to carry out experiments on their own interests.

Influence on Modern ECE Programs at Large:

Many programs use pedagogical documentation to show families what children have been participating in. Loose parts play is also becoming much more widespread in early childhood programs.

Questions for Your Reflection:

When you think of yourself as not just an educator, but a researcher of children, how does that influence your perspective on your work? What would you do differently as a researcher than as a teacher?

How does documentation differ from any other display of children’s work?

When you think about your environment, does it work with or against your program’s mission and vision? What would you like to change?

Early Childhood Education can have a lot of buzzwords and misunderstandings. This “Philosophy Spotlight” series intends to introduce you to the origins of a number of currently used philosophies directly from the writings of their founders and accomplished practitioners, as well as modern practices and ideas associated with these philosophies. Note that many of the philosophies and philosophers we reference in the US are Euro-centric in origin. I will do my best to integrate philosophies of development and learning from a more diverse body of knowledge, for the benefit of all children and providers. You’ll notice a significant amount of overlap between philosophies, as well as some stark differences. Use these articles to consider your own approach to early education, and maybe refine how you see you work and design your program. These are intended to be broad overviews; please see the references if you’d like to learn more about each one!

Origins: Dr. Montessori was a physician who worked with disabled children, who were at the time isolated in asylums and assumed to be incapable of anything worthwhile. She believed that these children had more potential to be educated, and so she set about creating a method of education (pedagogy) to be used specifically for children with disabilities, with her first school opening in 1898. She quickly realized that typically developing children could benefit from her ideas as well.

Modern Regulating Bodies/Standards: the American Montessori Society offers an accreditation program for Montessori schools, but AMS accreditation is not required for a program to call itself Montessori or use its practices.

Theories and Theorists: “The school must permit the free, natural manifestations of the child” – Maria Montessori

Young children’s options for activities are known as “work,” to give appropriate value to their actions. In modern use, preschool children’s work is separated into the areas of practical life, sensorial, language, mathematics, biology, geography, and fine arts.

Values:

Independence: children in Montessori classrooms are encouraged to work independently, from taking their materials off of the shelf, to competing the work, to placing it back on the shelf the way they found it. They are also taught to prepare and serve their own snacks and clean up after themselves.

Teachers are known as “guides” to highlight their role as a facilitator rather than director.

Children should have freedom to determine what they will work on and for how long.

Materials and environment should be beautiful and convey their importance to children.

What You Might Observe in a Montessori Classroom:

Montessori Materials: While the term “Montessori” is used to sell many items now, the Montessori materials are specific creations by Dr. Montessori and her predecessor, Dr. Édouard Séguin. These include items like The Pink Tower, the Hundred Board, and sandpaper letters. There may be only one way to use the materials. For example, a child may or may not be allowed to build a structure other than the Pink Tower with the Pink Tower blocks, depending on the program.

Like the materials are taught to children in sequence with predictable outcomes, art is taught to young children with discrete skills. Children learn about the colors and their relationship to each other on a color wheel; how to use scissors and glue; hole punching; taking rubbings; and many other fine art skills. Dr. Montessori did not write much about how art was to be used in the classroom, so her followers have interpreted this in a range of ways. In general, you will see art materials displayed in lessons, the same way you would see other materials displayed for children’s use.

Mixed-age grouping: Montessori classrooms typically have children of a variety of ages in them. Often you will find a toddler class for children from approximately 18 months until 30 months. After toddler they’ll move to pre-primary, for three- to six-year-olds. The idea behind this is to allow maximum flexibility for children to develop their abilities as they are ready, rather than on a closed schedule tied to chronological age.

Books (and all materials) emphasize reality. Because young children have trouble distinguishing fantasy from reality, Dr. Montessori believed that the books available to them should be rooted in reality, whether those are purely non-fiction or fictional books about the real world. In a traditional Montessori program, for example, you’re unlikely to see any books about talking animals or imaginary creatures. In general, fantasy play is discouraged, including dressing up in costumes. This does depend somewhat on the individual program and implementation.

Influence on Modern ECE Programs at Large:

Dr. Montessori is the primary reason so many early childhood environments have child-sized furniture. She was also one of the early pioneers of approaches that place emphasis on children being able to touch and manipulate the things they’re learning about. In Dr. Montessori’s Own Handbook, she writes about multicolored carpet squares for children to use for seating– a practice many early childhood spaces use today.

Questions for Your Reflection:

How do you see your role in the with children as compared to a classical Montessori guide?

How are materials used in your program?

What types of materials are available for children in your program?

What role do the children take in the maintenance and preparation of their environment?

When and how do you use explicit instruction to guide children? When and how do they have the opportunity to self-correct or use self-correcting materials?

Staying informed about recalls that might impact your materials is one way to be sure that the items you and your children use each day are safe for them. The Consumer Product Safety Commission is the organization that tracks safety issues as well as voluntary and mandatory recalls for all the products in our homes, like the pictured cups which were recalled for lead level violations in July 2023.

To search or browse recalls, visit Recalls | CPSC.gov

To sign up for email updates from the Consumer Product Safety Commission, which will notify you of recalls and safety alerts, go to: Subscriptions | CPSC.gov

Sharing this excellent webinar recording by the National Center on Early Childhood Development, Teaching, and Learning – Meaningful makeovers: Overcoming Challenges in the Family Child Care Setting.

While makeovers help make the environment look appealing to children and their families, the makeovers are also meaningful because of the environmental changes that support children’s learning and development.

Following along a provider as she makeover her space and gives you suggestions to create a change in your own space

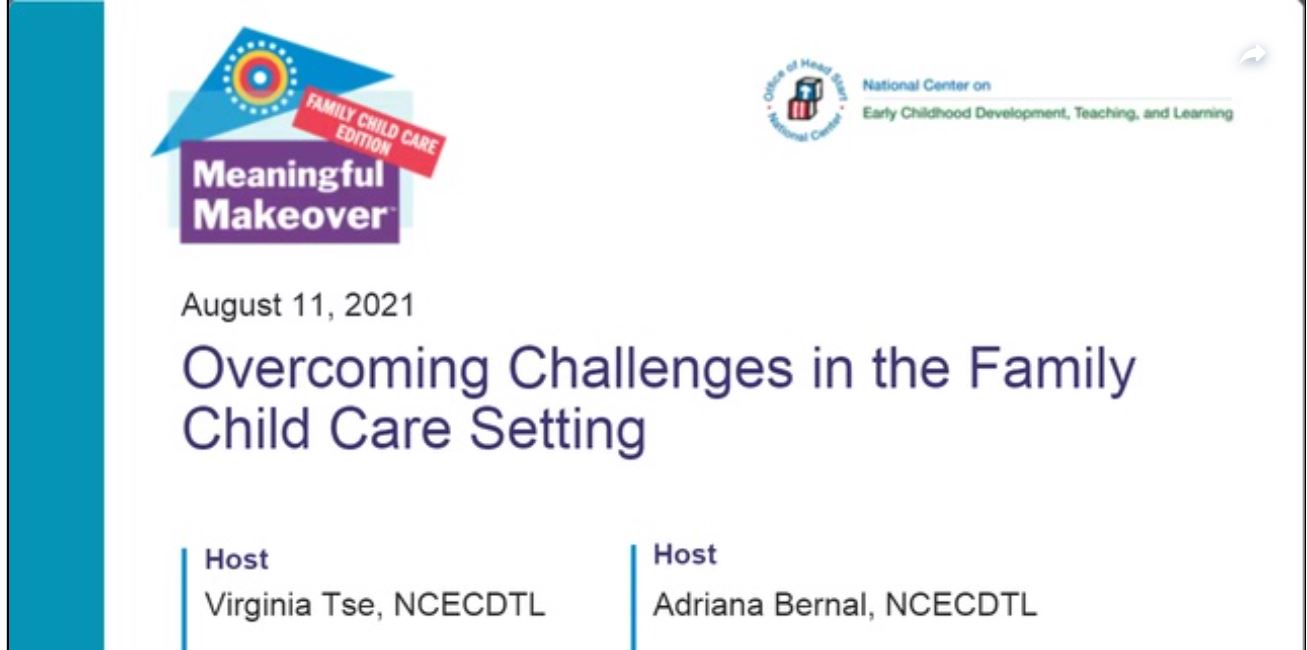

Playing with Nuts and bolts

Nuts and bolts may seem like a simple activity, but it provides children with many great opportunities to explore and build on their skills.

- Fine motor skills.

* Hand and eye coordination as children grasp and pick their selection of bolts and then attach the nuts and bolts.

* Twisting, pinching, rotating give fingers muscles a workout, skills needed later for writing

- Math skills

* Giving children a variety of bolts and nuts allows them the opportunity to sort, match, categorize as they make a selection and plan how to use them.

* Create patterns, count and describing of different attributes including size

- Language skills

* Back and forth conversation as they work with other children

* Exploration and explanation of their creation and learning to others

- Creativity

* So much creativity as children came up with new ways to create and play, testing their ideas.

- Sensory experience

* Different textures, weights, sizes, and materials can be incorporated, experimenting with touch and sound.

As we explore intentionality in incorporating nature into home-based care. We reached out to two family childcare professionals Diann Gano, Owner of Under the Ginkgo Tree Nature School, and Ashley Hugues, owner of Roots Nature School, to discuss the curriculum of a home-based nature program. We hope this conversation is a starting point to rethink nature in your program or help support your current practice.

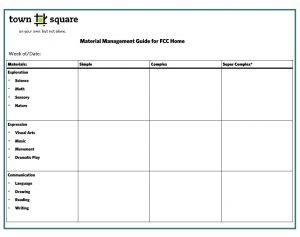

This Town Square created guide can be a helpful tool when planning activities for multiple ages and different learning domains.

You can learn more about learning domains and planning for multiple ages in the material modules

To use this document on your computer using Microsoft Word

If you would prefer a hard copy please download and print

Encourage your school age children to create a collection. They might take a container or bag and collect some things that they find in nature while outside, or they might collect a variety of stray parts or art and craft materials from around your home. Ask them to sort their collection in different ways and involve the other children in viewing their collection and trying to discover their sorting pattern. Challenge them to sort their collections in multiple ways and describe the rules they have established for sorting.

Goal: Children will practice sorting materials by different attributes and describing the different qualities of the materials in their collection.

Searching for good secondhand supplies and toys?

Finding and reusing safe, quality toys, and equipment can be easy if you know where to look. When I started my Family Childcare business 22 years ago, I used some of the toys I had purchased over the years for my sons. The toys were not on a recall list; I checked, and they were in perfect condition. I don’t remember what drew me to my first resale shop, but once I went, I fell in love. I was able to find good quality toys and equipment that others could no longer use. The resale shop locations came from the phone book, newspapers, word-of-mouth, and later, the Internet. My search for toys and equipment started with local resale shops. As I got more comfortable with the process, I ventured out to locations miles and miles away from home. The more you visit these sites, you will begin to learn what days toys and equipment come in, is sorted, marked, displayed, and further discounted. While searching the newspapers for resale shops, I saw an ad for a neighborhood garage sale, and that ad specifically mentioned “toys.” I couldn’t believe how many good; quality toys were available for purchase. You have to plan and be at locations early to get the best selection.