“¡Teddy se llevó mis trenes!”

“¡Te alejaste de ellos, y si no estás, otra gente puede utilizarlos!”.

“No, seguía usándolas. Sólo necesitaba mi botella de agua”.

La eterna lucha del niño en edad preescolar… necesitar un descanso, pero no querer perder los juguetes. ¡Y el educador que quiere que se recojan los materiales si nadie juega con ellos!

Introduce: la ficha de trabajo en curso.

Cada niño tiene la oportunidad de crear una tarjeta que le simbolice. Los niños mayores pueden querer escribir una letra o su nombre completo, los más pequeños pueden dibujar un símbolo o hacer un garabato.

No se trata sólo de practicar escribiendo nombres, como puede parecer a primera vista. Los niños aprenden la utilidad del lenguaje escrito y de los símbolos, y el poder de la comunicación escrita. Esto también les permite trabajar juntos para colaborar y compartir materiales, primero asumiendo la responsabilidad de su trabajo y luego hablando sobre cómo satisfacer las necesidades de todos.

Es útil predeterminar los parámetros de uso; ¿puede un niño utilizar una tarjeta de trabajo en curso para guardar algo durante la siesta? ¿Y hasta el día siguiente? ¿Pueden utilizarse sólo en un momento determinado del trabajo, o en cuanto se recogen los materiales? ¿Puede un niño tener varias obras en curso?

Para apoyar la capacidad de los niños para resolver problemas juntos, considera estas directrices iniciales como flexibles, y ayuda a los niños a pensar si están de acuerdo o no. Éste puede ser un tema para una reunión de grupo, o quizá sólo una discusión sobre la marcha.

Preguntas de reflexión

- ¿Las tarjetas de trabajo en curso resolverían un problema que tengo ahora mismo en mi entorno?

- ¿Cómo se los presentaría a los niños a mi cargo?

- ¿Cómo puedo hacer un seguimiento del uso de las tarjetas de trabajo en curso para realizar los ajustes necesarios?

Catalina y Alex, de cuatro años, juegan a ser “los malos”, persiguiéndose por turnos por el patio y discutiendo sus planes para “robar el tesoro”. Juan José, de tres años, está a unos metros de distancia, observando y a veces siguiendo a los otros niños cuando se alejan demasiado. Cuando la maestra Danika le pregunta a Juan José si quiere unirse a ellos, él le dice que “sólo está mirando”. A la profesora Danika le preocupa un poco su indecisión y toma nota mentalmente para ver si se une al juego más tarde.

El juego dramático, el juego creativo, el juego paralelo y otros son tipos de juego conocidos de los que se habla a menudo en relación con los niños pequeños. El juego de observación se discute menos. Es una de las etapas del juego de Parten, que suele observarse en niños de dos a tres años. A veces clasificado como un tipo de juego “no social” y, por tanto, menos discutido que el juego paralelo, asociativo y cooperativo, el juego de observación sigue teniendo un fuerte componente social. Es una de las formas en que los niños pequeños aprenden a relacionarse con los demás.

El juego de observación no tiene por qué ser silencioso; a menudo los jugadores observadores hablan o imitan las acciones de las personas a las que observan. La diferencia entre el juego de observación y el asociativo o cooperativo radica en el grado de participación. En el juego de observación, los niños seguirán visualmente y participarán verbalmente, pero no cogerán materiales relacionados con el juego ni parecerá que están jugando activamente. En el juego asociativo, los niños jugarán con los mismos materiales pero sin compartir ideas. En el juego cooperativo, los niños hablarán, compartirán materiales e ideas y se basarán en el trabajo de los demás.

¿Cuándo es un juego de espectadores y cuándo puede ser otra cosa?

Como todos los juegos, el juego del espectador es divertido. Si un niño observa mucho, pero no parece realmente implicado o expresivo, puede que no esté participando realmente en el juego del espectador, sino retrayéndose por otras razones. Si un niño observa cómo juegan los demás y nunca inicia su propio juego más activo, ya sea de forma independiente o con otros, observa más.

El comportamiento de juego de espectador suele surgir hacia los 2 años y medio, pero también puede darse en niños mayores, sobre todo cuando se están aclimatando a un nuevo entorno. Sin embargo, si un niño sólo participa en la medida que permite el juego de mirón durante días o semanas, puede que sea el momento de buscar formas de apoyar a ese niño para que se incorpore al juego social.

¿Cómo pueden los educadores apoyar el juego del espectador?

La mejor manera es darse cuenta y permitirlo. Saber que los niños pueden estar jugando de formas que a los adultos no les parecen un juego ayudará a mantener la perspectiva de que todo juego es valioso. Dejar espacio para el juego de los espectadores puede significar hacer menos, no más.

La profesora Danika, en el ejemplo anterior, podría asegurarse de que Juan José dispone de mucho espacio para observar a Catalina y Alex, así como de oportunidades para recrear sus ideas por su cuenta para procesar lo que ha visto.

Early Childhood Education can have a lot of buzzwords and misunderstandings. This “Philosophy Spotlight” series intends to introduce you to the origins of a number of currently used philosophies directly from the writings of their founders and accomplished practitioners, as well as modern practices and ideas associated with these philosophies. Note that many of the philosophies and philosophers we reference in the US are Euro-centric in origin. I will do my best to integrate philosophies of development and learning from a more diverse body of knowledge, for the benefit of all children and providers. You’ll notice a significant amount of overlap between philosophies, as well as some stark differences. Use these articles to consider your own approach to early education, and maybe refine how you see you work and design your program. These are intended to be broad overviews; please see the references if you’d like to learn more about each one!

Modern Regulating Bodies/Standards:

No regulating body exists to officially designate a program as play based.

Origins, Theories and Theorists:

Friedrich Froebel: Known as the “father of kindergarten,” Froebel believed that young children learn best through play and should be trusted to be in charge of their own play. The adult is present to support and guide children, ensuring their safety. Froebel is known for his “gifts” to children, sets of materials for children of different ages to use and learn from in their play. These gifts, in order, are:

- For infants, a set of six soft balls, in the primary and secondary colors (red, yellow, blue, orange, green, purple)

- Toddlers received a set with a wooden sphere, cube, and cylinder.

- After that, a two-inch cube made of eight, 1-inch blocks, designed to be taken apart and put together again.

- Around five years old, children would add rectangular prisms, with the dimensions of 1/2″ by 1″ by 2″, demonstrating the concept of fractions.

- One 3-inch cube made of 21 one-inch cubes, 6 half-cubes, and 12 quarter-cubes.

- The final classic gift is a set of 18 rectangular blocks, 12 flat square blocks, and 6 narrow columns. Concepts of scale, proportion, symmetry, and balance can be discovered with this set of blocks.

Quote: “A child that plays thoroughly, with self-active determination, persevering until physical fatigue forbids, will surely be a thorough, determined man, capable of self-sacrifice for the promotion of the welfare of himself or others.”

Dr. Peter Gray: a modern psychologist who writes about the role of play in children’s lives and the way we are all wired to learn through play. He states that true play has four characteristics:

- Play is self-chosen and self-directed

- Play is intrinsically motivated’ means are more valuable than ends

- Play is guided by mental rules

- Play is always creative and usually imaginative

Constructivism: a philosophy of education that states that people construct their own knowledge through interactions with the world around them as well as with and through other people.

Values:

Long blocks of time for children to play uninterrupted: Children need time to get involved in their play, plan, and create scenarios. At least 30 minutes and ideally 90 minutes at a time.

Creative expression: children are encouraged to express their ideas in a variety of ways through their play as well as in varied art media.

Educators and other adults are observers and sometimes co-players, and design environments for children to play in, but do not control the play scenarios. They do, however, offer materials, scaffold interactions, and interject when a play becomes hazardous either to children’s physical or emotional wellbeing.

What You Might Observe in a Program with Emergent Curriculum:

Educators will be close to the children but not necessarily playing with them unless invited in.

Schedule is arranged with few transitions, and large blocks of time for children to play and develop their ideas.

Many art and writing materials available to encourage children’s self-expression.

Open-ended materials for play. While explicitly representative items may be present (train sets, dolls, kitchens), there will likely be many more items that don’t have a pre-assigned purpose, such as large pieces of fabric, wood blocks, or collections of natural materials such as stones and leaves.

Influence on Modern ECE Programs at Large:

Many early childhood programs value children’s free and creative play, with a focus on open-ended materials.

NAFCC level one accreditation requires the children have the opportunity to direct their own free play for at least 30 minutes at a time, for at least one full hour in a half day of care.

The presence of unit blocks is directly from Froebel.

Questions for Your Reflection:

How do children play in your program? What are their preferred games, themes, and materials?

What is the adult’s role in play in your program?

How do your daily and weekly routines support children’s engaging in free play, both individually and in groups?

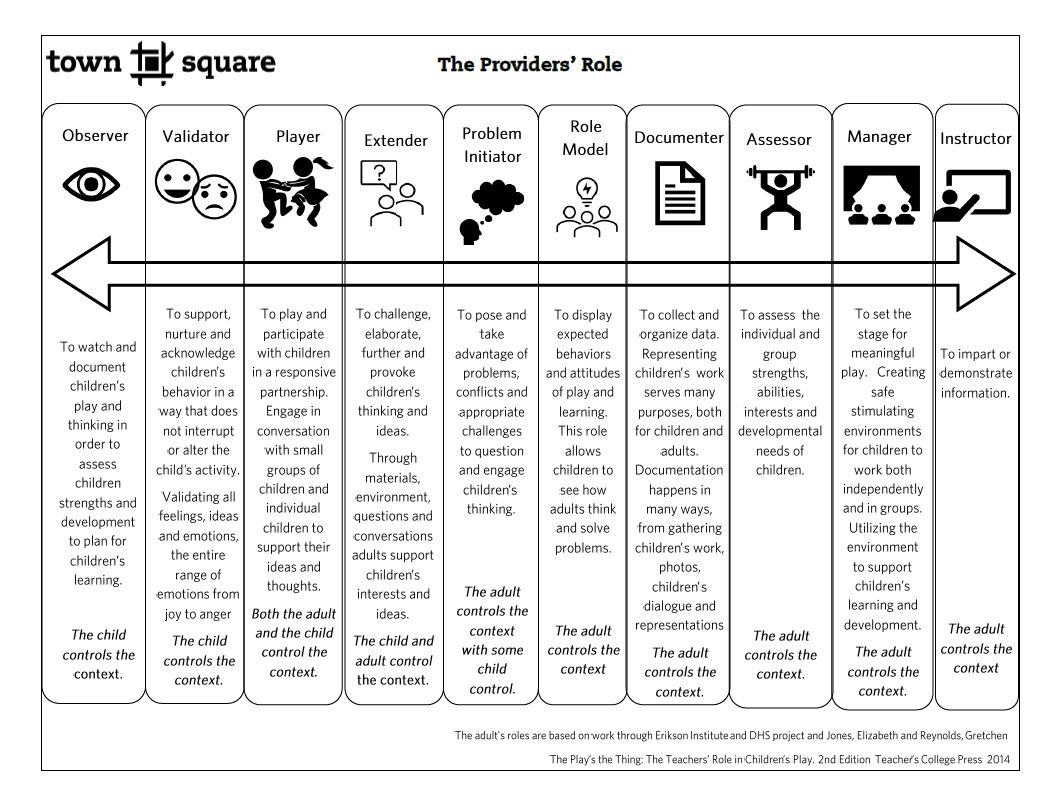

Educating and caring for young children requires that providers take on various roles to support meaningful and playful experiences.

The roles providers take on include…

Observer – To watch and document children’s play and thinking in order to assess children’s strengths and development to plan for children’s learning.

Validator – To support, nurture and acknowledge children’s behavior in a way that does not interrupt or alter the child’s activity.

Player – To play and participate with children in a responsive partnership.

Extender – To challenge, elaborate, further and provoke children’s thinking and ideas.

Problem initiator – To pose and take advantage of problems, conflicts, and appropriate challenges to question and engage children’s thinking.

Role model – To display expected behaviors and attitudes of play and learning.

Documenter – To collect and organize data.

Assessor – To assess children’s individual and group strengths, abilities, interests, and developmental needs.

Manager – To set the stage for meaningful play.

Instructor – To impart or demonstrate information.

It is essential to note that these roles are not static, where one day you decide to be an observer and another extender. Instead, the roles change throughout the day, creating balance.

What if one of the answers to reducing inequality and addressing mental health concerns among young children is as simple as providing more opportunities to play? A growing body of research and several experts are making the case for play to boost the well-being of young children as the pandemic drags on—even as concerns over lost learning time and the pressure to catch kids up grow stronger.

Play is so powerful, according to a recent report by the LEGO Foundation, that it can be used as a possible intervention to close achievement gaps between children ages 3 to 6. The report looked at 26 studies of play from 18 countries. It found that in disadvantaged communities, including those in Bangladesh, Rwanda and Ethiopia, children showed significantly greater learning gains in literacy, motor and social-emotional development when attending child care centers that used a mix of instruction and free and guided play. That’s compared to children in centers with fewer opportunities to play, especially in child-led activities, or that placed a greater emphasis on rote learning. This is important, the report’s authors noted, as it shows free and guided play opportunities are possible even in settings where resources may be scarce. “Play can exist everywhere,” said Bo Stjerne Thomsen, chair of Learning Through Play at the LEGO Foundation. “It’s the experience. Testing and trying out new ideas…It’s really about the state of mind you’re in while playing.”

The report found that play enabled children to progress in several domains of learning, including language and literacy, social emotional skills and math. The varieties of play include games, open play where children can freely explore and use their imaginations and play where teachers provide materials and some parameters. The findings suggest that rather than focusing primarily on academic outcomes and school readiness, play should be used as a strategy to “tackle inequality and improve the outcomes of children from different socio-economic groups.” That also means opportunities to play should be considered a marker of quality in early childhood programs, the authors concluded. Stjerne Thomsen said the authors have not defined an ideal amount of play as they believe it can be embedded throughout the day. More importantly, he added, is that teachers are trained to facilitate free play and guided play opportunities. “Play is often defined as recreation…not serious or practical,” said Stjerne Thomsen. Instead, many schools are focused on academic skills and standardized assessments, he added.

The findings of the report, which echo years of related research on the emotional physical and cognitive benefits of play, are notable considering that in America access to play spaces is lacking in many lower-income and rural communities. That became more noticeable during the pandemic when outdoor activities became one of the safest options for activities. Experts say opportunities to play are essential for helping kids process their feelings and changes in their life, especially after the past year of disruption and trauma. “Play is absolutely an essential part of the healing process,” said Tena Sloan, a licensed therapist and the vice president of early childhood mental health consultation and training at Kidango, a nonprofit with a network of child care centers in California. “We need to give [kids] these other ways to diffuse their stress and express themselves.” That includes, she adds, “being outside and having that freedom to play.”

Some nationwide initiatives have been working for years to create play space equity and ensure kids have access to safe, outdoor spaces, even in high-density or rural areas. The non-profit KABOOM! has built or improved more than 17,000 play spaces nationwide and has partnered with communities to build unique play spaces based on local needs, including obstacle courses for teens and “play installations” that turn everyday spaces, like bus stops, laundromats and sidewalks, into places where children can play. During the pandemic, the non-profit continued to build playgrounds and sports parks across the country with the help of volunteers; it also created “play kits” that schools could send home to children, allowing them opportunities to play in and around their home.

Play can help bring “normalcy back,” said Jen DeMelo, director of special projects at Kaboom! “This pandemic has brought to light that [play] is not a luxury, this is a necessity,” DeMelo added. “We need this. Kids need this to thrive.”

This story Twenty-six studies point to more play for young children was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

Use masking tape to create roads on the floor for matchbox or hot wheel type cars. Children can ‘drive’ cars along the roads and create dramatic play scenarios. Children can add other accessories, such as road signs, farm animals, train toys, etc. to extend the activity.

Goal: Children will move vehicles around the masking tape roads and engage in dramatic play.

You may have heard about the idea of loose parts and how wonderful they are for encouraging children’s exploration and play. This handout created by Penn State Extension offers tips for using loose parts, examples of types of loose parts, and outlines some of the benefits of play with loose parts. Chances are you have several loose parts for children to explore already in your home, so get them out and get ready to play!