Cuando una familia se compromete con un programa de cuidado infantil, declara que confía en que el proveedor mantendrá a su hijo seguro y sano, y le proporcionará un entorno educativo y afectuoso en el que crecer. Éste puede ser el primer paso de una relación sólida y duradera cuando los educadores se toman el tiempo necesario para construirla intencionadamente con las familias de los niños a su cargo.

¿Por qué es beneficioso establecer relaciones entre educadores y familias? A menudo, los educadores de guarderías son la primera experiencia de una familia en la que un adulto ajeno a la familia cuida de su hijo. Como introducción al cuidado extrafamiliar, los educadores infantiles marcan la pauta de la forma en que las familias se comprometen con toda la educación de su hijo. Preparar el escenario con relaciones profesionales cálidas y afectuosas ayudará a las familias a comprometerse con todos los sistemas en los que participarán con su hijo.

Una relación sólida entre la familia y el educador infantil también beneficia directa e inmediatamente al niño. Los educadores de guarderías familiares y las familias son las personas que pasan más tiempo con el niño y están en mejor posición para abogar por él y apoyar su crecimiento y desarrollo. Cuando las familias y los educadores construyen juntos relaciones sólidas, pueden comunicarse más eficazmente cuando surgen preocupaciones o desacuerdos. Mantener relaciones con las familias ofrece a los educadores la oportunidad de comprender mejor a cada niño, y puede dar a las familias la comodidad necesaria para participar en el programa del niño y compartir los intereses y habilidades con el educador y los niños.

¿Cómo aprovechan los educadores de guarderías familiares esta oportunidad para conectar con las familias y establecer esas relaciones profesionales?

- Empieza antes del primer día: Aunque las familias ya tienen mucho papeleo que hacer para inscribirse, algunos educadores añaden una página “para conocerte” en la que las familias pueden responder a preguntas que ayudarán al proveedor a comprender la historia, las preferencias y las necesidades de sus familias. Algunos ejemplos de preguntas son

- ¿Qué lengua(s) oye y habla tu hijo en casa?

- ¿Quién vive en casa de tu hijo, incluidas las mascotas? ¿A quién visitan con frecuencia?

- ¿Qué os gusta hacer en familia?

- ¿Con qué suele jugar tu hijo?

- Cuenta una historia: Los días pueden ser ajetreados, pero tomar nota proactivamente de algo que el niño haya dicho o disfrutado durante el día para comunicarlo a las familias en el momento de la partida mantendrá esa relación. Dar prioridad a la comunicación cara a cara, aunque sea para ti un minuto o dos cada vez, facilitará las conversaciones más importantes cuando sean necesarias. Esto no tiene por qué ocurrir todos los días con todos los niños, pero los primeros días que un niño está en un programa son especialmente importantes para establecer esta conexión.

- Invítalos: Cuando los niños se interesan por un tema que uno de los padres conoce, o surge la oportunidad de hacer una excursión, invitar a las familias individualmente o en grupo para que compartan su experiencia o supervisen una excursión creará vínculos y recuerdos.

Para reflexionar:

¿Qué acción puedo añadir a mi día que ayude a construir esas relaciones recíprocas con las familias?

Nonviolent communication is “a language of compassion.” While we don’t often think of our words, or anyone else’s, as violent, the emotional harm that we do to others and have done to us is real. Once we can accept that all behavior from children is communication, we are ready to take on a bigger challenge: learning and internalizing that behavior in the form of spoken, written, and body language from adults is communication too.

Because of the close personal nature of our work, it’s almost inevitable that at some point we will have a disagreement with a family member. But these disagreements don’t have to cause long-term damage to relationships. When we are skilled in nonviolent communication, we can strengthen our relationships with families through compassionate and thoughtful conversations, even when the conversations themselves are uncomfortable.

Consider a common source of tension between families and providers: when a child is too ill to attend child care, or becomes ill during the day.

From the provider’s perspective, one ill child will lead to more ill children, and when the care is provided in your home, it can impact your whole family. That might mean your children are sick, or you have to spend even more time cleaning and sanitizing than usual. It makes group care difficult: a sick child won’t want to play, won’t be in a cooperative mood, and may throw off the group routine with heightened need for sleep.

From the family’s perspective, a sick child may mean missing work when they are out of paid leave or in a probationary period. It can be harder to see that a child is ill when they are at home; it’s easier to meet the child’s needs individually rather than in a group setting, and the child is more comfortable at home and may just be happier with their family then they were at child care. Families who are stressed financially might be upset that they are paying for time they can’t use.

Making the call can be anxiety-inducing. Some providers might prefer to avoid the conflict altogether, and not say anything, or passively suggest that the family “keep an eye on” the child for symptoms. Other providers might start on the attack “Why did you send your child here when they’re clearly sick?!” Using non-violent communication urges a different path: First, try to anticipate the other person’s needs. While you can’t make a difference in how the person’s employer will respond to them needing to leave early to pick up a sick child, you can start with empathy. Then state your own need clearly.

“Hi Johanna; I’m sorry to interrupt you at work, I know you just started your new job. I’m calling to let you know that Jamari is running a fever and will need to be picked up before nap time. After he’s been fever-free for 24 hours, we’ll be excited to welcome him back!”

When you begin by acknowledging the other party’s needs, it tells them that you’re aware of what you’re asking. Following by phrasing your own needs clearly and in a positive way (i.e. with a direction, not just “don’t bring him back until he’s better) allows the other person to understand what is expected of them and plan accordingly. Finishing with a personal message also helps to convey that this isn’t a decision you made because you don’t want the child there, but because he’s uncomfortable and you have the responsibility of reducing the risk of contagious illness for all children in your care.

Using the framework of nonviolent communication reduces the room for misunderstandings and for professional boundaries to become personal. You can even use these practices when writing policies– another way to proactively anticipate conflict with families and clarify each party’s responsibilities in the child care setting.

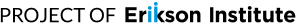

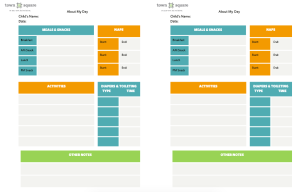

Give families a snap shot of their child’s day in care! Prints two sheets per page.

Sharing ideas on how to use social media – specifically Facebook groups to communicate with families