Making Grand-Friends

The concept of “non-family intergenerational interactions” is centered around the simple idea that old and young can bring new energy, knowledge and enthusiasm to each others’ lives. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, we had a relationship with a retirement community, where several of their residents would travel to our preschool regularly to read and play with the children. Since restrictions have been lifted, the Caterpillar Clubhouse Nature Preschool children have been traveling to the retirement community instead, every other week, to visit their grand-friends.

I was in awe that the simple presence of our preschoolers made such a difference in these grand-friends lives. I noticed how the kids completely accepted the physical and mental differences around them with such natural grace. And gained a sense of connection across the generations. Too often we underestimate the power of a hug, smile and children’s laughter…. I believe in the respect and dignity of life for people of all ages, young and old. This core belief is the thread interwoven through the fabric of our program.

What the groups do when they meet can be as relaxed as playing with play dough, a balloon game or reading a book together.

Valuing Older People

Older adults have a need to contribute to the next generation, and that doing so can give older people feelings of accomplishment or success, rather than stagnation, as they age. Intergenerational activities show elders that they are valued as individuals that still possess lifelong skills, rather than being passive recipients of care. One lady who attended the care facility told me that you don’t think about your age when you are in the company of young children. The little ones brought a new sense of vibrancy and fun to the center, and the focus was no longer on watching time pass but on living in the moment.

These days traditional families are separated by distance, time and lack of understanding between generations, but programs that bring children and older adults together could change the whole of society’s outlook.

Early Childhood Education is about building relationships. Research shows that students who have healthy intergenerational relationships have better self-confidence as well as a greater sense of empathy and tolerance. Children also develop a positive sense of aging and the interactions between generations reduce fear of older adults. Relationships between the children and elders also reduce fear of various abilities and disabilities.

Quote of the day: Grand-friend: I didn’t even know I needed that hug until I just received it.

Preschool students, Primrose residents find friendship in one another | News | kokomotribune.com

As part of our social emotional learning curriculum, we read a story about a different social-emotional concept using sight, touch, and sound to engage children and solidify the skill-building process.

I always incorporate a stuffed animal that correlates to a different social or emotional need. For example, unicorns for creativity, bears for feeling love, sloths slowing down, snail feeling brave. My goal is to tell a story or read a book I find about that SEL goal and pass the stuffed animal around and help them believe in themselves and their abilities. To remind them we can get through hard times, and we don’t have to do it alone.

Daily we work on positive affirmations and the idea that their opinions about themselves matter. We’ve also talked about how to handle difficult situations and when to ask for help. Being a teacher, I’m doing everything in my power to help guide, kind, empathetic, and strong kids.

Social Emotional Learning is instilling feelings of self-worth into our kids. We use affirmations in response to many situations, like conflict-resolution needs, self-esteem needs, and emotional regulation needs to name a few. And using affirmations daily I notice the kids pulling out these types of positive sayings on their own, without my initiation.

The specific skills the children are learning include:

- Interaction — physical touch, eye contact, and playfulness

- Connection — reading positive affirmations and having them repeat them to you (if possible)

- Reflection — practicing the learned concepts and skills

As teachers we honor the emotional lives of children and enable them to find the words to express themselves as they come to terms with their complex feelings.

In early care and education, family child care plays a vital role in nurturing young minds and providing a supportive environment for children’s growth and development. Family child care offers a unique setting where children receive personalized attention in a home-like atmosphere. One of the key factors contributing to the success of family childcare is the environment in which it takes place. In this blog post, we’ll explore how to set up an enriching environment for family childcare, fostering learning, creativity, and emotional well-being.

The physical space of a family child care setting should be carefully designed to promote safety, comfort, and exploration. Consider creating distinct areas for different activities such as play, learning, and quiet areas. Use child-sized furniture and equipment to encourage independence and engagement. Neutral colors, child created artwork, and age-appropriate toys can stimulate curiosity and imagination.

Play is a crucial aspect of early childhood development, serving as a vehicle for learning and socialization. Incorporate a variety of materials and activities that encourage exploration, problem-solving, and creativity. For example, provide open-ended toys like blocks, puzzles, and art supplies that allow children to experiment and express themselves freely. Outdoor play areas are also beneficial for gross motor development and sensory exploration.

Consistency and structure are essential for young children, providing a sense of security and predictability. Establishing a daily routine that includes time for play, learning, meals, and rest helps children feel comfortable and helps manage behavior. Displaying visual schedules can help children understand and anticipate the day’s activities. Flexibility is key, but maintaining a general rhythm can contribute to a positive childcare environment for both children and caregivers.

Family child care offers the opportunity for meaningful relationships to grow between caregivers, children, and families. Create a warm and welcoming atmosphere where children feel valued, respected, and supported. Take the time to listen to their thoughts and feelings and engage in meaningful interactions that promote language development and emotional intelligence. Building strong partnerships with families through open communication and collaboration is also essential for providing consistent and responsive care.

As caregivers, it’s crucial to stay informed about best practices in early childhood education and to continually reflect on and improve practices. Attend training sessions, workshops, and conferences to stay updated on the latest research and trends. Seek feedback from families and colleagues and be open to trying new approaches that better meet the needs of the children in your care.

Family childcare offers a unique and valuable option for early care and education, providing children with a nurturing and supportive environment where they can learn, grow, and thrive. By thoughtfully designing the physical space, promoting learning through play, establishing routines, cultivating positive relationships, and committing to continuous learning and improvement, caregivers can create an enriching environment that sets the stage for lifelong success.

Provider Stephanie McKinstry’s preschoolers arrived one day to a challenge: could they build bridges for bears to cross? How about a bridge big and strong enough for all of their bears to stand on at once?

The children got to work constructing their bridges from cups and popsicle sticks, arranging different shapes and patterns.

During construction, some bridge builders sang variations of “Going on a Bear Hunt”, like “Going on a Fish Hunt” because they knew that’s what bears like to eat!

If you want to do this in your own home, you’ll just need the following:

(if you don’t have counting bears, you can use buttons, game pieces, pompoms– really anything that isn’t too tricky to balance!)

Indiana providers: can you spot the Indiana Early Learning Standards being addressed with this activity?

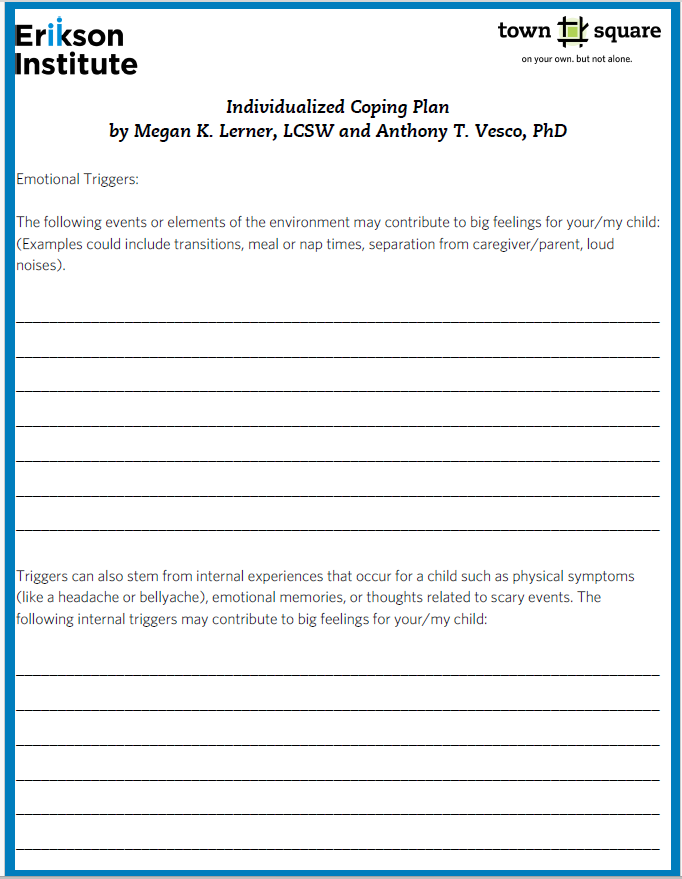

This resource, from Megan K. Lerner, LCSW and Anthony T. Vesco, PhD, will help you work with families and children who are struggling with behavioral issues.

There are two versions of this resource, one to hand write and one to complete on the computer.

There are lots of common birds in Indiana that stick around for winter. Many of these are colorful favorites that evoke a winter feeling. Our two picks were Cardinals and Blue Jays.

Bird feeders are lively places during the winter months and their presence is important. Feeding winter birds can be a fun and educational activity for kids; they can learn about different species while also learning about their habitats, diets, and winter survival tools.

How We Explored Our Winter Birds:

- Create a bird observation center in your play area by setting up bird feeder stations. You can build your own from recycled materials such as milk cartons, recycled jugs or pinecones or purchase pre-made bird feeders.

- Next decide what type of bird seed you want to use. Investigate what types of food will attract which birds, and offer the children a choice of which they’d like to try– or fill one feeder with one type, and a second with another, and encourage the children to compare which birds they see around each.

- Placing feeders by a window for indoor viewing is an excellent idea for those cold winter days. You can create a chart on a whiteboard or large sheet of paper so they can check off birds they see on it.

- After a few weeks, compile your observations looking for patterns in birds observed at your feeders at different times of the day. Discuss the results.

For more bird-bassed fun, try these:

- Make bird seed play dough for your table activity or sensory table. Try picking up seeds with different shaped tongs and notice which is the most successful for different kinds of seeds.

- Go on a bird feather hunt and research to identify the bird it came from. Record children’s hypotheses and look for a live match!

Within the Reggio Emilia approach, and now in many early childhood programs, the environment where children spend their time is typically called the third teacher. The environment helps determines the flow of the day, what children learn and how they interact with one another. Having the right amount, variety, and types of materials in an early childhood classroom will make the day run more smoothly and will be more engaging for the children, thus in turn will make it easier for the teacher.

Knowing the why, when, and how to rotate toys is important and a worthwhile task, based upon information gathered through child observations. Through observations of the children in care, we can determine if, when, and what types of materials need to be rotated in the environment. The provider knows the children in their care very well and soon can see patterns emerge that will help the provider make specific adjustments in the environment.

Let’s consider some of the reasons why we rotate toys in a childcare environment.

A child may have mastered a certain skill and by changing specific materials in the classroom we can help scaffold the child to the next skill level. Children learn through facing appropriate challenges, but it’s important to make the challenge achievable. We don’t want the child to feel frustrated or lose interest. A skilled teacher is able to observe students and notice these small changes and find materials that will spark curiosity and interest. We may want to teach a new skill. Placing new toys and materials in the classroom can help a child learn a new skill, such as sequencing, stacking, or balancing. We may also want to challenge that skill and make it slightly more difficult by adding something new to use. Safety is top priority so make sure that items placed in the environment are safe for all ages of the children in the classroom. This can be challenging in multi age programs but can be overcome with a little planning and thought. A child’s individual interests will also play a part in the items we choose. We know that children will play with things that interest them. Having materials of interest will mean the children will explore and play with things that interest them and that are relatable and familiar to them. Common household items that children are familiar with are good to add when possible.

Now let’s take a look at when we might remove certain materials from the classroom environment. When children have lost interest, aren’t playing with as intended or are mistreating the materials, this is a good time to remove them and find materials that the children are interested in. Intended uses of toys and materials may vary from item to item. I believe that a toy does not necessarily have to be used exclusively for its intended purpose. I believe children should be able to use their imagination and creativity and use items in different ways, not just the way intended from the manufacturer. Items that are distracting and stress inducing should be removed. Some children are more sensitive to certain colors, sounds, and even how much is available in the environment for the children at one time. Remember less is more.

Finally, how we display items in the environment helps convey to the children what is expected of them and where items belong. Neatly placing items on a shelf helps children put things away on their own. Labeling shelves and baskets make clean up a breeze. They can also see and reach what they would like to play with, and this allows for independence. Placing similar items together on the shelf in an aesthetically pleasing way, where children can see them shows we care about our materials and toys, and they deserve a place in the space. Don’t over crowd the environment. Less really is more in childcare. If too many choices are available to children, they don’t play well with any of them. Choose items that interest the children and things they are familiar with and see in their day to day lives. We want these items to be relatable to children and familiar. Children want to use “real” things they see in their everyday lives. If teaching a theme, we may want to choose items that relate to the theme being taught or based upon the current season. Rotating 1-2 things a week and making adjustments as needed is less stressful on children than changing everything at one time.

Creating an organized and inviting environment is not difficult. With a little planning and time, you can create a relaxing and organized childcare space to enjoy for children and teachers alike.

- Personally acknowledge and greet each family and child, with a smile as they enter the room.

Doing this simple task helps build meaningful and respectful relationships with families. It’s the first interaction the family may have each day and will go a long way in helping families feel welcome. Calling the parent by their name (unless otherwise specified by the parent) and their child by their own name, makes it personal. We want parents to know we are happy to see them and their child and greeting them by their first name is much nicer and more personal than just saying “hello”. If you are unsure how to pronounce their name, it’s best to politely mention you are unsure and ask them how to say it and repeat it back.

- Have daily and ongoing conversations with families.

Each day talk to the family and share something their child did that was positive. Either a new skill learned, or an interaction with another child you observed that was especially nice are examples. Try to be engaging, smile and actively listen. Daily conversations build trust and allows for other conversations to evolve over time, allowing you to learn about the family and their child. When trust is built, families are more comfortable sharing information that may be helpful in meeting the child’s needs and in some cases the family’s needs as well.

- Make sure all families and all children are represented.

Displays around the classroom should represent all children. They should depict varying abilities, languages, and cultures. This need to be done in a non-stereotypical way. The environment should include a combination of pictures, books, dolls, music, and household items that are familiar to children and things they would find in their own home and community. Ask families to bring in family photos of all family members, doing activities they enjoy as a family. Display and make classroom books with them. Displays should be at both child height and parents’ height. Offering seating for adults to sit shows families that they are welcome to stay awhile, and you care about their comfort.

- Provide ways for families to volunteer.

When families can participate one way or another in the childcare program, they feel invested and included. Childcare programs have many different task to manage throughout the year, why not get the help of the families. Parents usually are very happy to lend a hand or offer skills or services they may have. It’s also fun to get the whole family involved. Some ways parents can volunteer might be, a spring or fall clean up on the playground, repairing equipment, sewing things for the classroom, reading a book to the children, or doing a cooking activity with a small group of children. Remember that not all families will be able nor want to volunteer in the classroom and we want to be respectful of this. Providing a list of things, parents can work on at home will allow these families to also feel valued and connected too. Remember part of feeling welcome is knowing you are valued no matter how or if you choose to participate.

- Provide resources and support for families.

Create a specific area in the childcare program where parents can go to get resources pertinent to child development, parenting, health and safety, product recall information and child nutrition as well as social service supports and free events available in your area. Providing resources that pertain to parenting and child development will let parents know that you care about their family outside the walls of the childcare. The location should stay consistent so parents will know where to find these resources and can visit without the help of staff. Providing a small lending library if you’re able, may be useful too. Keep this area uncluttered and organized so parents will want to visit and can find what they are looking for. Remove outdated information in a timely manner.

La Educación Infantil puede tener muchas palabras de moda y malentendidos. Esta serie de ” Enfoques de Filosofía ” intenta presentar el origen de una serie de filosofías que se utilizan actualmente, directamente de los textos de sus fundadores y practicantes expertos, y también prácticas e ideas modernas asociadas con estas filosofías. Tenga en cuenta que muchas de las filosofías y filósofos a los que hacemos referencia en EE.UU. son de origen eurocéntrico. Haré todo lo posible por integrar filosofías del desarrollo y el aprendizaje de un conjunto más diverso de conocimientos, en beneficio de todos los niños y proveedores. Observará que las filosofías se superponen en gran medida, al igual que algunas diferencias muy marcadas. Utilice estos artículos para reflexionar sobre su propio enfoque de la educación infantil y, tal vez, para afinar la manera en que percibe su trabajo y diseña su programa. Estos artículos son sólo una visión general; si desea obtener más información sobre cada uno de ellos, consulte las referencias.

Orígenes: Después de que Italia fuese destruida como poder fascista durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, hubo un movimiento para reconstruir el país de forma que apoyara a sus ciudadanos en la búsqueda de la libertad frente a la opresión. La primera escuela de Reggio Emilia fue construida por familias que buscaban crear una nueva escuela para sus hijos mientras reconstruían su comunidad. Rápidamente se convirtieron en una red de centros preescolares y guarderías durante los años sesenta y setenta. En 1991, Newsweek nombró a la escuela Diana, uno de los centros preescolares de Reggio Emilia, una de las mejores escuelas del mundo.

Organismos reguladores/estándares modernos: El término ” Método Reggio Emilia ” es una marca registrada, lo que hace que muchos programas describan su filosofía como ” Inspirado en Reggio “, aunque no existe ningún organismo regulador fuera de Italia que controle el uso del término. Una escuela no puede ser certificada como escuela Reggio Emilia, ni un profesor puede ser un profesor Reggio Emilia certificado. Existen organizaciones en la Red Internacional que promueven la difusión de información sobre el método Reggio Emilia, pero no actúan como reguladores.

Teorías y teóricos:

Loris Malaguzzi se considera como el fundador del método Reggio Emilia. Era psicólogo titulado en pedagogía y anteriormente había cofundado una escuela para niños con discapacidades y dificultades de aprendizaje. Mientras trabajaba allí, se le propuso colaborar con la nueva red de centros preescolares y guarderías.

Valores:

Los niños participan activamente en su proceso de crecimiento: Cada niño puede y tiene derecho a crear su propia experiencia como individuo y miembro de un gran colectivo.

Progettazione/Diseño: La educación se moldea a través del diseño de entornos, la participación y el diseño de situaciones de aprendizaje. No ocurre en el mismo grado en los programas prediseñados o en los currículos prefabricados.

Los cien lenguajes: Los cien lenguajes de los niños es una metáfora del potencial de los niños y de sus procesos de pensamiento y creatividad. Es un valor central para honrar todas las formas de autoexpresión de los niños igualmente.

Sin dudas, los cien están allí: Un poema de Loris Malaguzzi (traducido por M. Pilar Martínez-Agut and Carmen Ramos Hernando)

El niño

está hecho de cien.

El niño tiene cien lenguas

cien manos

cien pensamientos

cien maneras de pensar

de jugar y de hablar

cien siempre cien

maneras de escuchar

de sorprenderse de amar

cien alegrías

para cantar y entender

cien mundos

que descubrir

cien mundos

que inventar

cien mundos

que soñar.

EL niño tiene

cien lenguas

(y además de cien cien cien)

pero le roban noventa y nueve.

La escuela y la cultura

le separan la cabeza del cuerpo.

Le dicen:

de pensar sin manos

de actuar sin cabeza

de escuchar y no hablar

de entender sin alegría

de amar y sorprenderse

sólo en Pascua y en Navidad.

Le dicen:

que descubra el mundo que ya existe

y de cien le roban noventa y nueve.

Le dicen:

que descubra el mundo que ya existe

y de cien le roban noventa y nueve.

Le dicen:

que el juego y el trabajo

la realidad y la fantasía

la ciencia y la imaginación

el cielo y la tierra

la razón y el sueño

son cosas que no van juntas

Y le dicen

que el cien no existe

El niño dice:

«en cambio el cien existe».

Participación: A los niños se les invita a participar en las relaciones, en el aula y en la comunidad. De este modo, los niños adquieren el “sentimiento de solidaridad, responsabilidad e inclusión, y producen cambios y nuevas culturas” (Niños de Reggio).

El aprendizaje como proceso de construcción, subjetivo y en grupo: Cada niño construye su propio conocimiento, a través de la conversación, la investigación y el debate.

Investigación educativa: Los adultos que interactúan con niños deben verse a sí mismos como investigadores y utilizar su documentación como investigación acerca de los niños, los grupos de niños y el aprendizaje. Los educadores deben animarse a seguir construyendo y reconstruyendo sus conocimientos y prácticas.

Documentación educativa: Adultos y niños toman vídeos, fotos y muestras del trabajo para documentar el aprendizaje de los niños. Estos documentos se utilizan para provocar el debate entre los educadores, los niños y entre los educadores y los niños.

Organización: El tiempo, el espacio y el trabajo se organizan para reflejar los valores de la escuela y los proyectos.

Entorno y espacios: Tanto los espacios interiores como los exteriores están diseñados y organizados para interactuar con las personas que los ocupan, dar forma a las experiencias de aprendizaje e inspirar el pensamiento y la creatividad. El cuidado y mantenimiento del entorno es fundamental, por lo que la estética del espacio intenta crear placer y alegría en las personas que lo utilizan.

Formación/Crecimiento profesional: El crecimiento profesional es un derecho de cada educador y de todo el grupo. En Reggio Emilia, el desarrollo profesional es parte del tiempo laboral de los educadores, y ocurre dentro de las reuniones de equipo y en el contexto más amplio de la ciudad, nacional e internacional.

Evaluación: Las escuelas deben ser evaluadas con frecuencia por sus coordinadores, educadores, miembros de la comunidad y familias, para garantizar que satisfacen las necesidades de los niños y las familias.

Lo que podría observar en un programa inspirado en Reggio:

Muchos programas inspirados en Reggio Emilia ponen un gran énfasis en las artes, especialmente en las representaciones visuales y la planificación, junto con la exploración guiada de materiales de artes visuales. Es probable que haya documentación del trabajo de los niños colgada para niños y adultos. Con frecuencia, los niños de los programas inspirados en Reggio utilizan más “piezas sueltas” en vez de juguetes tradicionales. Siguiendo el valor de Reggio de diseñar, se les ofrece a los niños “provocaciones”, que son conjuntos de materiales diseñados para que los niños exploren y experimenten con ellos para provocar su pensamiento y ampliar sus intereses. Las provocaciones pueden ser una cubeta con pequeñas pelotas y rampas; crayones sin envoltorio, hojas y papel fino para hacer grabados; cajas, cinta adhesiva y crayones para crear; o cualquier otra cosa que los niños puedan utilizar para llevar a cabo experimentos sobre sus propios intereses.

Influencia en los programas modernos de educación infantil en general:

Muchos programas utilizan documentación pedagógica para mostrar a las familias lo que han estado haciendo los niños. El juego de piezas sueltas también está mucho más extendido en los programas de educación infantil.

Preguntas para la reflexión:

Cuando se considera a sí mismo no sólo como educador, sino como investigador de los niños, ¿cómo influye esto en su perspectiva de trabajo? ¿Qué haría diferente siendo investigador que siendo educador?

¿Cómo se diferencia la documentación del resto de las muestras del trabajo de los niños?

Cuando piensa en su entorno, ¿favorece o perjudica la misión y la visión de su programa? ¿Qué le gustaría cambiar?

What can a child learn from a fight? A lot, with the right opportunities.

A dispute with a peer can teach a child about how to voice their own needs, how to weigh the needs of another, and how to compromise and problem-solve with others.

In the Japanese practice of Mimamoru (literally, “watch and protect”), early childhood practitioners are trained to intervene minimally and later than many American early childhood educators would expect, while still closely observing children’s fights. The principle behind this is that while the adult’s role is to protect the children, children need the experience of navigating social complexity to build their social skills. A child who hits another and is then sent away from the activity learns that the adult nearby doesn’t want them to hit but does not learn how to get their needs met. When that same adult stop in, checks on the child who was hit, and helps both children verbalize their wants and needs, both children have the opportunity to understand each other and find a solution.

Perhaps the more difficult situation here is one where the attacks aren’t physical, but emotional. Relational aggression (e.g. “You’re not my friend!” or “You can’t come to my birthday party!”) can be more difficult to intervene in, and harder to spot. This also tends to peak in late preschool and early elementary years as children refine their definition of friendships and understand what it means to be a friend, as well as the power that comes from being included or excluding others.

In either act of aggression, how can the educator offer a learning opportunity instead of simply managing or shutting down the behavior? People are born with the desire to connect, and emotional resilience, as well as a guiding moral voice. What needs to be scaffolded are the skills to advocate for oneself and listen to and hypothesize about others’ perspectives.

First, look at the purpose of adult interventions: no one wants the children to be hurt, physically or emotionally. But in the same way that learning to walk comes with a few tumbles, learning to be a friend and participant in a community comes with its own missteps. If children cannot learn from each other and us when they’re small, they won’t have the experience to navigate social relationships as they become more complex.

This is the platform on which larger concepts of restorative justice are built; instead of punishing the person who harmed another, we work to ensure that the person who was hurt is comforted, and the person who did the hurting has the resources to avoid doing it again.

Questions for your reflection:

- What was your first reaction when you thought about waiting to intervene?

- What are your current intervention strategies when children are fighting?

- How could you integrate a “pause” before intervening?

- What else could you do to support children in learning conflict mediation?