“Teddy took my trains!”

“You walked away from them, and if you’re not there, other people can use them!”

“No, I was still using them. I just needed my water bottle.”

The perennial struggle of the preschooler… needing to take a break, but not wanting to lose toys. And the educator who wants materials picked up if no one is playing with them!

Enter: the work in progress card.

Each child has the opportunity to create a card that symbolizes them. Older children might want to write a letter or their whole name, younger children might draw a symbol or scribble.

This isn’t just practice writing names, as it may appear on the surface. Children learn about the utility of written language and symbols, and the power of written communication. This also empowers them to work together to collaborate and share materials, first by taking ownership of their work and then by talking through how to meet everyone’s needs.

It’s helpful to predetermine the parameters for use; can a child use a work in progress card to save something through nap time? What about until the next day? Can they be used only on at a certain point in the work, or as soon as materials are collected? Can one child have multiple works in progress?

To support children’s ability to problem solve together, consider these initial guidelines as flexible, and support children in thinking through whether they agree or disagree. This may be a topic for a group meeting, or perhaps just a discussion on the fly.

Reflection Questions

- Would work-in-progress cards solve a problem I have in my setting right now?

- How would I introduce these to the children in my care?

- How can I follow up on the use of work in progress cards to make adjustments as needed?

Four-year-olds Catherine and Alex are playing “bad guys,” taking turns chasing each other around the yard and discussing their plans to “steal the treasure.” Three-year-old Juan Jose is a few feet away, watching and sometimes following the other children when the get too far away. When Teacher Danika asks Juan Jose if he’d like to join them, he tells her that he’s “just watching.” Teacher Danika is a little worried about his hesitance and makes a mental note to see if he joins in play later.

Dramatic play, creative play, parallel play, and more are familiar types of play that are discussed often in regard to young children. Onlooker play is less discussed. It is one of Parten’s stages of play, typically seen in two- to three-year-olds. Sometimes classified as a type of “non-social” play and therefore less discussed than parallel, associative, and cooperative play, onlooker play still has a strong social component. It is one way that young children learn how to engage with others.

Onlooker play doesn’t need to be silent; often onlooking players will talk to or mimic the actions of the people they’re observing. The distinction between onlooker and associative or cooperative play lies in the degree of participation. In onlooker play, children will visually follow and verbally engage but not pick up materials that relate to the game or look like they’re actively playing. In associative play, children will play with the same materials but not sharing ideas. Cooperative play will involve children talking, sharing materials and ideas, and building off of each other’s work.

When is it onlooker play, and when might it be something else?

Like all play, onlooker play is enjoyable. If a child is doing a lot of watching, but doesn’t really seem engaged or expressive, they might not really be participating in onlooker play but instead withdrawing for other reasons. If a child is watching others play and never initiating their own more active play, whether independently or with others, observe more.

Onlooker play behavior usually emerges around 2 1/2, but can happen in older children as well, especially when they are acclimating to a new environment. However, if a child is only engaging to the extent that onlooker play allows for days or weeks, it may be time to look into ways to support that child in entering social play.

How can educators support onlooker play?

The best way is to notice and allow it! Knowing that children may be playing in ways that don’t look like play to adults will help keep perspective that all play is valuable. Making space for onlooker play might mean doing less, not more.

Teacher Danika in the example above could be sure Juan Jose has plenty of space to watch Catherine and Alex, as well as opportunities to recreate their ideas on his own to process what he saw.

When providers encounter children engaging in play with troubling themes, it’s important to understand how to interact with the children in their play, when and how to interrupt, and how to talk to families about our observations. This one-page downloadable/printable document from mental health professionals Megan Lerner, LCSW and Anthony T. Vesco, PhD, can help prepare you for these difficult situations.

Early Childhood Education can have a lot of buzzwords and misunderstandings. This “Philosophy Spotlight” series intends to introduce you to the origins of a number of currently used philosophies directly from the writings of their founders and accomplished practitioners, as well as modern practices and ideas associated with these philosophies. Note that many of the philosophies and philosophers we reference in the US are Euro-centric in origin. I will do my best to integrate philosophies of development and learning from a more diverse body of knowledge, for the benefit of all children and providers. You’ll notice a significant amount of overlap between philosophies, as well as some stark differences. Use these articles to consider your own approach to early education, and maybe refine how you see you work and design your program. These are intended to be broad overviews; please see the references if you’d like to learn more about each one!

Modern Regulating Bodies/Standards:

No regulating body exists to officially designate a program as play based.

Origins, Theories and Theorists:

Friedrich Froebel: Known as the “father of kindergarten,” Froebel believed that young children learn best through play and should be trusted to be in charge of their own play. The adult is present to support and guide children, ensuring their safety. Froebel is known for his “gifts” to children, sets of materials for children of different ages to use and learn from in their play. These gifts, in order, are:

- For infants, a set of six soft balls, in the primary and secondary colors (red, yellow, blue, orange, green, purple)

- Toddlers received a set with a wooden sphere, cube, and cylinder.

- After that, a two-inch cube made of eight, 1-inch blocks, designed to be taken apart and put together again.

- Around five years old, children would add rectangular prisms, with the dimensions of 1/2″ by 1″ by 2″, demonstrating the concept of fractions.

- One 3-inch cube made of 21 one-inch cubes, 6 half-cubes, and 12 quarter-cubes.

- The final classic gift is a set of 18 rectangular blocks, 12 flat square blocks, and 6 narrow columns. Concepts of scale, proportion, symmetry, and balance can be discovered with this set of blocks.

Quote: “A child that plays thoroughly, with self-active determination, persevering until physical fatigue forbids, will surely be a thorough, determined man, capable of self-sacrifice for the promotion of the welfare of himself or others.”

Dr. Peter Gray: a modern psychologist who writes about the role of play in children’s lives and the way we are all wired to learn through play. He states that true play has four characteristics:

- Play is self-chosen and self-directed

- Play is intrinsically motivated’ means are more valuable than ends

- Play is guided by mental rules

- Play is always creative and usually imaginative

Constructivism: a philosophy of education that states that people construct their own knowledge through interactions with the world around them as well as with and through other people.

Values:

Long blocks of time for children to play uninterrupted: Children need time to get involved in their play, plan, and create scenarios. At least 30 minutes and ideally 90 minutes at a time.

Creative expression: children are encouraged to express their ideas in a variety of ways through their play as well as in varied art media.

Educators and other adults are observers and sometimes co-players, and design environments for children to play in, but do not control the play scenarios. They do, however, offer materials, scaffold interactions, and interject when a play becomes hazardous either to children’s physical or emotional wellbeing.

What You Might Observe in a Program with Emergent Curriculum:

Educators will be close to the children but not necessarily playing with them unless invited in.

Schedule is arranged with few transitions, and large blocks of time for children to play and develop their ideas.

Many art and writing materials available to encourage children’s self-expression.

Open-ended materials for play. While explicitly representative items may be present (train sets, dolls, kitchens), there will likely be many more items that don’t have a pre-assigned purpose, such as large pieces of fabric, wood blocks, or collections of natural materials such as stones and leaves.

Influence on Modern ECE Programs at Large:

Many early childhood programs value children’s free and creative play, with a focus on open-ended materials.

NAFCC level one accreditation requires the children have the opportunity to direct their own free play for at least 30 minutes at a time, for at least one full hour in a half day of care.

The presence of unit blocks is directly from Froebel.

Questions for Your Reflection:

How do children play in your program? What are their preferred games, themes, and materials?

What is the adult’s role in play in your program?

How do your daily and weekly routines support children’s engaging in free play, both individually and in groups?

Play is vital for children; through play, children can develop, explore, and practice new skills. This Town square created a resource aids in developing a better understanding of the skills and learning involved in children’s play.

You might think that I’m just playing, but…

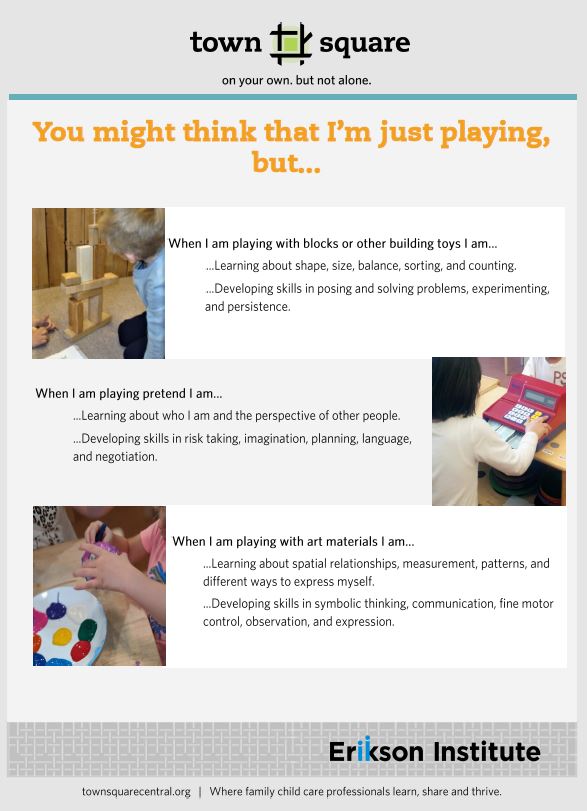

Playing with Nuts and bolts

Nuts and bolts may seem like a simple activity, but it provides children with many great opportunities to explore and build on their skills.

- Fine motor skills.

* Hand and eye coordination as children grasp and pick their selection of bolts and then attach the nuts and bolts.

* Twisting, pinching, rotating give fingers muscles a workout, skills needed later for writing

- Math skills

* Giving children a variety of bolts and nuts allows them the opportunity to sort, match, categorize as they make a selection and plan how to use them.

* Create patterns, count and describing of different attributes including size

- Language skills

* Back and forth conversation as they work with other children

* Exploration and explanation of their creation and learning to others

- Creativity

* So much creativity as children came up with new ways to create and play, testing their ideas.

- Sensory experience

* Different textures, weights, sizes, and materials can be incorporated, experimenting with touch and sound.

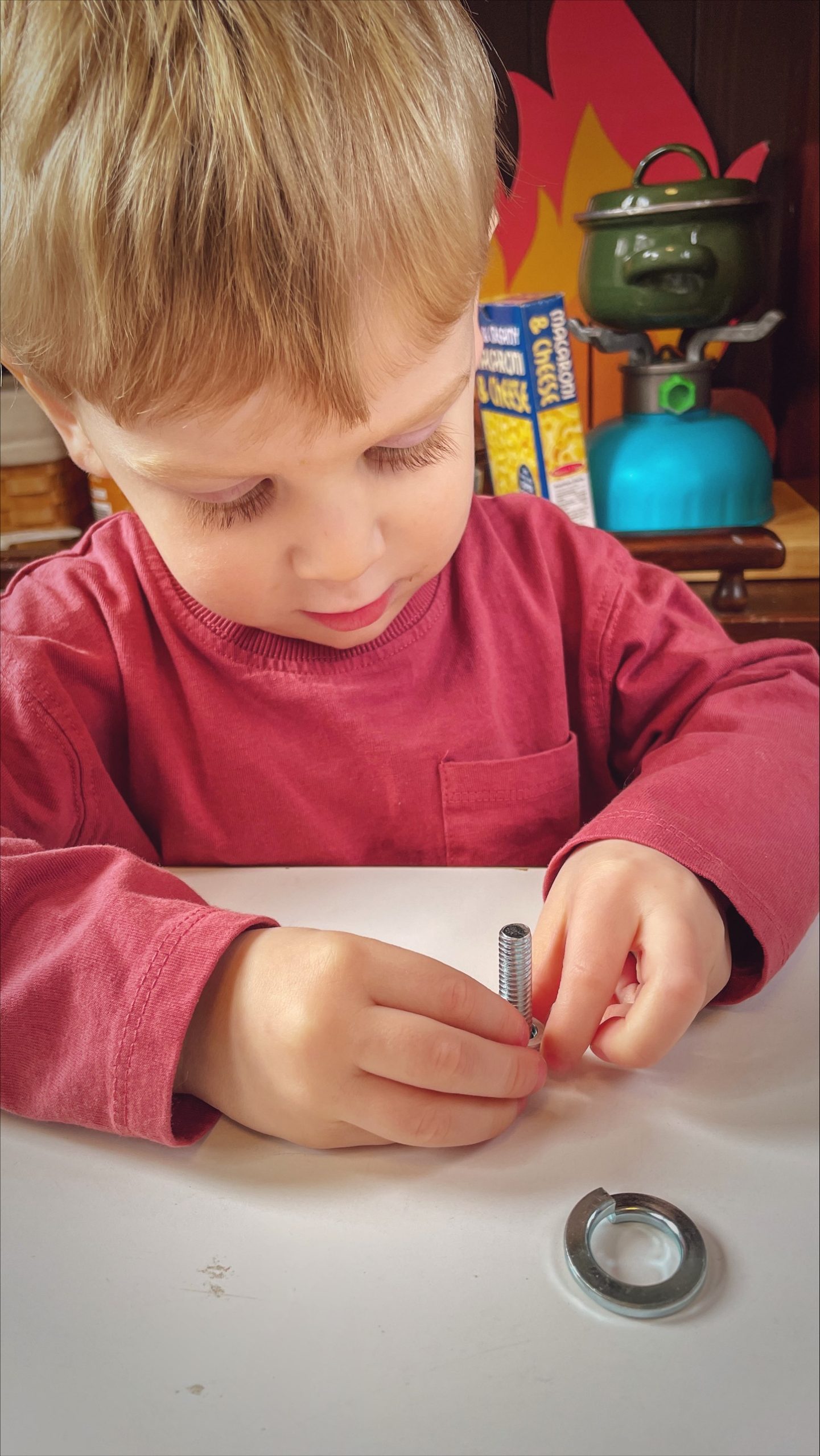

Educating and caring for young children requires that providers take on various roles to support meaningful and playful experiences.

The roles providers take on include…

Observer – To watch and document children’s play and thinking in order to assess children’s strengths and development to plan for children’s learning.

Validator – To support, nurture and acknowledge children’s behavior in a way that does not interrupt or alter the child’s activity.

Player – To play and participate with children in a responsive partnership.

Extender – To challenge, elaborate, further and provoke children’s thinking and ideas.

Problem initiator – To pose and take advantage of problems, conflicts, and appropriate challenges to question and engage children’s thinking.

Role model – To display expected behaviors and attitudes of play and learning.

Documenter – To collect and organize data.

Assessor – To assess children’s individual and group strengths, abilities, interests, and developmental needs.

Manager – To set the stage for meaningful play.

Instructor – To impart or demonstrate information.

It is essential to note that these roles are not static, where one day you decide to be an observer and another extender. Instead, the roles change throughout the day, creating balance.

What if one of the answers to reducing inequality and addressing mental health concerns among young children is as simple as providing more opportunities to play? A growing body of research and several experts are making the case for play to boost the well-being of young children as the pandemic drags on—even as concerns over lost learning time and the pressure to catch kids up grow stronger.

Play is so powerful, according to a recent report by the LEGO Foundation, that it can be used as a possible intervention to close achievement gaps between children ages 3 to 6. The report looked at 26 studies of play from 18 countries. It found that in disadvantaged communities, including those in Bangladesh, Rwanda and Ethiopia, children showed significantly greater learning gains in literacy, motor and social-emotional development when attending child care centers that used a mix of instruction and free and guided play. That’s compared to children in centers with fewer opportunities to play, especially in child-led activities, or that placed a greater emphasis on rote learning. This is important, the report’s authors noted, as it shows free and guided play opportunities are possible even in settings where resources may be scarce. “Play can exist everywhere,” said Bo Stjerne Thomsen, chair of Learning Through Play at the LEGO Foundation. “It’s the experience. Testing and trying out new ideas…It’s really about the state of mind you’re in while playing.”

The report found that play enabled children to progress in several domains of learning, including language and literacy, social emotional skills and math. The varieties of play include games, open play where children can freely explore and use their imaginations and play where teachers provide materials and some parameters. The findings suggest that rather than focusing primarily on academic outcomes and school readiness, play should be used as a strategy to “tackle inequality and improve the outcomes of children from different socio-economic groups.” That also means opportunities to play should be considered a marker of quality in early childhood programs, the authors concluded. Stjerne Thomsen said the authors have not defined an ideal amount of play as they believe it can be embedded throughout the day. More importantly, he added, is that teachers are trained to facilitate free play and guided play opportunities. “Play is often defined as recreation…not serious or practical,” said Stjerne Thomsen. Instead, many schools are focused on academic skills and standardized assessments, he added.

The findings of the report, which echo years of related research on the emotional physical and cognitive benefits of play, are notable considering that in America access to play spaces is lacking in many lower-income and rural communities. That became more noticeable during the pandemic when outdoor activities became one of the safest options for activities. Experts say opportunities to play are essential for helping kids process their feelings and changes in their life, especially after the past year of disruption and trauma. “Play is absolutely an essential part of the healing process,” said Tena Sloan, a licensed therapist and the vice president of early childhood mental health consultation and training at Kidango, a nonprofit with a network of child care centers in California. “We need to give [kids] these other ways to diffuse their stress and express themselves.” That includes, she adds, “being outside and having that freedom to play.”

Some nationwide initiatives have been working for years to create play space equity and ensure kids have access to safe, outdoor spaces, even in high-density or rural areas. The non-profit KABOOM! has built or improved more than 17,000 play spaces nationwide and has partnered with communities to build unique play spaces based on local needs, including obstacle courses for teens and “play installations” that turn everyday spaces, like bus stops, laundromats and sidewalks, into places where children can play. During the pandemic, the non-profit continued to build playgrounds and sports parks across the country with the help of volunteers; it also created “play kits” that schools could send home to children, allowing them opportunities to play in and around their home.

Play can help bring “normalcy back,” said Jen DeMelo, director of special projects at Kaboom! “This pandemic has brought to light that [play] is not a luxury, this is a necessity,” DeMelo added. “We need this. Kids need this to thrive.”

This story Twenty-six studies point to more play for young children was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

Loose parts are materials that can be used in a variety of ways. It is very likely that you have things that can be used for loose parts play already around, such as bottle caps, rocks, pinecones, etc. This handout was created collaboratively between Town Square and the Early Math Collaborative at Erikson Institute as a resource for the Oak Park Collaboration for Early Childhood Symposium.

Some fun ideas for indoor large motor play for programs with limited access to an outdoor space, bad weather, or to share with families

- Laser maze – Works best in a hallway, but a door frame can work for a shorter obstacle. Using painter’s tape, streamers or yarn, web it between the walls or door frame. Have children walk through without touching the tape.

- Ball toss – Use softballs or bean bags and baskets or boxes. Arrange the boxes in a straight line. Have children take turns hitting the target. You can also use a staircase and have a box on each step, for older children use different size boxes to challenge them.

- Movement dice – Create a die with different movements shown on each side. Have children do the movement they roll or do a sequence of movements based on several rolls. For an added challenge, add a second die with numbers on each side for the number of times they must repeat that move. Simply print the pattern below, draw the movements, cut and fold the pattern into dice and start playing!

Town Square Paper dice

- Hopscotch – Using painters tape or washi tape create your version of a hopscotch board.

- Sticky wall – Place contact paper or thick tape on a wall, sticky side out. Have children throw pompoms or balls of paper to the target. For younger children, lower it down and allow them to place items on the sticky side.

- Ball race – using a box and a few balls, cut out holes on the bottom of a box, then have children then move the box allowing the ball to fall through. For older children, have them work with a larger box in teams, or create many holes and ask the children to try to keep the ball from falling through a hole.

- Bubble wrap road – Lay a path of bubble wrap on the floor and have children use balls or cars on the road. For younger children, have them walk or crawl on the bubble road.

- Balancing course – To work on balance, have children hold a spoon with a ball or pompom, then walk, jump, skip, to the other side of the room. Try a paper plate on their head, or holding toilet paper roll with a ball on top for extra challenge.

- Magnetic fishing– Create a simple magnetic fishing game with paper clips or bobby pins, paper or felt, straws and a magnet. Have children take turns fishing

Printable version Indoor large motor activities