What can a child learn from a fight? A lot, with the right opportunities.

A dispute with a peer can teach a child about how to voice their own needs, how to weigh the needs of another, and how to compromise and problem-solve with others.

In the Japanese practice of Mimamoru (literally, “watch and protect”), early childhood practitioners are trained to intervene minimally and later than many American early childhood educators would expect, while still closely observing children’s fights. The principle behind this is that while the adult’s role is to protect the children, children need the experience of navigating social complexity to build their social skills. A child who hits another and is then sent away from the activity learns that the adult nearby doesn’t want them to hit but does not learn how to get their needs met. When that same adult stop in, checks on the child who was hit, and helps both children verbalize their wants and needs, both children have the opportunity to understand each other and find a solution.

Perhaps the more difficult situation here is one where the attacks aren’t physical, but emotional. Relational aggression (e.g. “You’re not my friend!” or “You can’t come to my birthday party!”) can be more difficult to intervene in, and harder to spot. This also tends to peak in late preschool and early elementary years as children refine their definition of friendships and understand what it means to be a friend, as well as the power that comes from being included or excluding others.

In either act of aggression, how can the educator offer a learning opportunity instead of simply managing or shutting down the behavior? People are born with the desire to connect, and emotional resilience, as well as a guiding moral voice. What needs to be scaffolded are the skills to advocate for oneself and listen to and hypothesize about others’ perspectives.

First, look at the purpose of adult interventions: no one wants the children to be hurt, physically or emotionally. But in the same way that learning to walk comes with a few tumbles, learning to be a friend and participant in a community comes with its own missteps. If children cannot learn from each other and us when they’re small, they won’t have the experience to navigate social relationships as they become more complex.

This is the platform on which larger concepts of restorative justice are built; instead of punishing the person who harmed another, we work to ensure that the person who was hurt is comforted, and the person who did the hurting has the resources to avoid doing it again.

Questions for your reflection:

- What was your first reaction when you thought about waiting to intervene?

- What are your current intervention strategies when children are fighting?

- How could you integrate a “pause” before intervening?

- What else could you do to support children in learning conflict mediation?

Early Childhood Education can have a lot of buzzwords and misunderstandings. This “Philosophy Spotlight” series intends to introduce you to the origins of a number of currently used philosophies directly from the writings of their founders and accomplished practitioners, as well as modern practices and ideas associated with these philosophies. Note that many of the philosophies and philosophers we reference in the US are Euro-centric in origin. I will do my best to integrate philosophies of development and learning from a more diverse body of knowledge, for the benefit of all children and providers. You’ll notice a significant amount of overlap between philosophies, as well as some stark differences. Use these articles to consider your own approach to early education, and maybe refine how you see you work and design your program. These are intended to be broad overviews; please see the references if you’d like to learn more about each one!

Origins: After Italy had been destroyed as a fascist power during World War II, there was a movement to rebuild the country in a way that would support its citizens in pursuit of freedom from oppression. The first Reggio Emilia school was built by families seeking to create a new school for their children as they rebuilt their community. They quickly grew into a network of preschools and infant toddler centers through the 1960s and 70s. In 1991, Newsweek called the Diana school, one of Reggio Emilia’s preschools, one of the best schools in the world.

Modern Regulating Bodies/Standards: The term “Reggio Emilia Approach” is trademarked, leading to many programs describing their philosophy as “Reggio Inspired”, although there is no regulating body outside of Italy that controls the use of the term. A school cannot be certified as a Reggio Emilia school, nor can a teacher be a certified Reggio Emilia teacher. There are organizations in the International Network that further the spread of information about the Reggio Emilia approach, but do not serve as regulators.

Theories and Theorists:

Loris Malaguzzi is considered the founder of the Reggio Emilia approach. He was a psychologist trained in pedagogy and had previously co-founded a school for children with disabilities and learning difficulties. While working there, he was approached to collaborate with the new network of preschools and infant-toddler centers.

Values:

Children are active protagonists in their growing processes: Every child can and has the right to create their own experiences as an individual and member of a larger group.

Progettazione/Designing: Education is shaped by the design of environments, participation, and the design of learning situations. It does not happen to the same degree in predesigned programs or curricula that are premade.

The hundred languages: The Hundred Languages of Children are a metaphor for the potential of children and their thinking and creative processes. It is a central value to honor all of children’s forms of self-expression equally.

No way. The hundred is there: A Poem by Loris Malaguzzi (translated by Lella Gandini)

No way. The hundred is there.

The child

is made of one hundred.

The child has

a hundred languages

a hundred hands

a hundred thoughts

a hundred ways of thinking

of playing, of speaking.

A hundred always a hundred

ways of listening

of marveling, of loving

a hundred joys

for singing and understanding

a hundred worlds

to discover

a hundred worlds

to invent

a hundred worlds

to dream.

The child has

a hundred languages

(and a hundred hundred hundred more)

but they steal ninety-nine.

The school and the culture

separate the head from the body.

They tell the child:

to think without hands

to do without head

to listen and not to speak

to understand without joy

to love and to marvel

only at Easter and at Christmas.

They tell the child:

to discover the world already there

and of the hundred

they steal ninety-nine.

They tell the child:

that work and play

reality and fantasy

science and imagination

sky and earth

reason and dream

are things

that do not belong together.

And thus they tell the child

that the hundred is not there.

The child says:

No way. The hundred is there.

Participation: Children are welcomed to participate in relationships, in the classroom and community. This is to give children the “feeling of solidarity, responsibility, and inclusion, and produce changes and new cultures” (Reggio Children).

Learning as a process of construction, subjective and in groups: Every child constructs their own knowledge, through conversation, research, and discussion.

Educational research: Adults interacting with children should see themselves as researchers and use their documentation as research into children, groups of children, and learning. Educators should be encouraged to continue constructing and reconstructing their knowledge and practices.

Educational documentation: Adults and children take videos, photos, and work samples to document the learning the children are engaging in. These documents are used to provoke discussion and through between educators, between children, and between educators and children together.

Organization: Time, space, and work are all organized to reflect the values of the school and projects.

Environment and spaces: Interior and exterior spaces are all designed and organized to interact with the people in the space, shape learning experiences, and inspire thought and creativity. Care of the environment is critical, and maintaining the aesthetics of the space is intended to create pleasure and joy in the people who use the space.

Formation/Professional growth: Professional growth is the right of individual educators and the whole group. In Reggio Emilia, professional development is part of educators’ working time, and occurs within staff meetings and the larger city, national, and international context.

Evaluation: The schools should be evaluated frequently by their coordinators, educators, community members, and families to ensure that they are meeting the needs of the children and families.

What You Might Observe in a Reggio Inspired Program:

Many Reggio Emilia inspired programs place a heavy emphasis on the arts, particularly visual representations and planning, along with guided exploration of visual arts materials. There will likely be documentation of children’s work hanging up for children and adults. Oftentimes, children in Reggio Inspired programs use more “loose parts” than traditional toys. As part of the Reggio value of designing, children are offered “provocations” which are curated sets of materials designed for children to explore and experiment with to provoke their thinking and extend their interests. Provocations can look like a tray with small balls and ramps; unwrapped crayons, leaves, and thin paper for printmaking; boxes, tape, and crayons to create with; or anything else that children might use to carry out experiments on their own interests.

Influence on Modern ECE Programs at Large:

Many programs use pedagogical documentation to show families what children have been participating in. Loose parts play is also becoming much more widespread in early childhood programs.

Questions for Your Reflection:

When you think of yourself as not just an educator, but a researcher of children, how does that influence your perspective on your work? What would you do differently as a researcher than as a teacher?

How does documentation differ from any other display of children’s work?

When you think about your environment, does it work with or against your program’s mission and vision? What would you like to change?

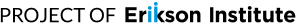

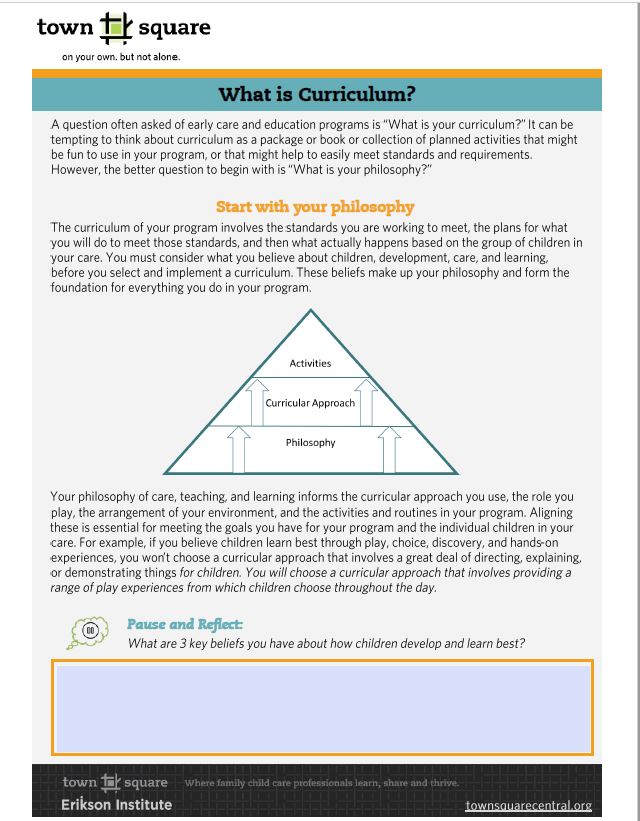

A philosophy of how children learn is one component of program design. A provider’s philosophy of how children learn will impact their learning environment, routines, activities they offer, and interactions with children. A philosophy is typically influenced by early childhood theorists, but every provider’s philosophy will be informed by their own experiences with children and their own upbringing and culture.

Early Childhood Education can have a lot of buzzwords and misunderstandings. This “Philosophy Spotlight” series intends to introduce you to the origins of a number of currently used philosophies directly from the writings of their founders and accomplished practitioners, as well as modern practices and ideas associated with these philosophies. Note that many of the philosophies and philosophers we reference in the US are Euro-centric in origin. I will do my best to integrate philosophies of development and learning from a more diverse body of knowledge, for the benefit of all children and providers. You’ll notice a significant amount of overlap between philosophies, as well as some stark differences. Use these articles to consider your own approach to early education, and maybe refine how you see you work and design your program. These are intended to be broad overviews; please see the references if you’d like to learn more about each one!

Origins: Dr. Montessori was a physician who worked with disabled children, who were at the time isolated in asylums and assumed to be incapable of anything worthwhile. She believed that these children had more potential to be educated, and so she set about creating a method of education (pedagogy) to be used specifically for children with disabilities, with her first school opening in 1898. She quickly realized that typically developing children could benefit from her ideas as well.

Modern Regulating Bodies/Standards: the American Montessori Society offers an accreditation program for Montessori schools, but AMS accreditation is not required for a program to call itself Montessori or use its practices.

Theories and Theorists: “The school must permit the free, natural manifestations of the child” – Maria Montessori

Young children’s options for activities are known as “work,” to give appropriate value to their actions. In modern use, preschool children’s work is separated into the areas of practical life, sensorial, language, mathematics, biology, geography, and fine arts.

Values:

Independence: children in Montessori classrooms are encouraged to work independently, from taking their materials off of the shelf, to competing the work, to placing it back on the shelf the way they found it. They are also taught to prepare and serve their own snacks and clean up after themselves.

Teachers are known as “guides” to highlight their role as a facilitator rather than director.

Children should have freedom to determine what they will work on and for how long.

Materials and environment should be beautiful and convey their importance to children.

What You Might Observe in a Montessori Classroom:

Montessori Materials: While the term “Montessori” is used to sell many items now, the Montessori materials are specific creations by Dr. Montessori and her predecessor, Dr. Édouard Séguin. These include items like The Pink Tower, the Hundred Board, and sandpaper letters. There may be only one way to use the materials. For example, a child may or may not be allowed to build a structure other than the Pink Tower with the Pink Tower blocks, depending on the program.

Like the materials are taught to children in sequence with predictable outcomes, art is taught to young children with discrete skills. Children learn about the colors and their relationship to each other on a color wheel; how to use scissors and glue; hole punching; taking rubbings; and many other fine art skills. Dr. Montessori did not write much about how art was to be used in the classroom, so her followers have interpreted this in a range of ways. In general, you will see art materials displayed in lessons, the same way you would see other materials displayed for children’s use.

Mixed-age grouping: Montessori classrooms typically have children of a variety of ages in them. Often you will find a toddler class for children from approximately 18 months until 30 months. After toddler they’ll move to pre-primary, for three- to six-year-olds. The idea behind this is to allow maximum flexibility for children to develop their abilities as they are ready, rather than on a closed schedule tied to chronological age.

Books (and all materials) emphasize reality. Because young children have trouble distinguishing fantasy from reality, Dr. Montessori believed that the books available to them should be rooted in reality, whether those are purely non-fiction or fictional books about the real world. In a traditional Montessori program, for example, you’re unlikely to see any books about talking animals or imaginary creatures. In general, fantasy play is discouraged, including dressing up in costumes. This does depend somewhat on the individual program and implementation.

Influence on Modern ECE Programs at Large:

Dr. Montessori is the primary reason so many early childhood environments have child-sized furniture. She was also one of the early pioneers of approaches that place emphasis on children being able to touch and manipulate the things they’re learning about. In Dr. Montessori’s Own Handbook, she writes about multicolored carpet squares for children to use for seating– a practice many early childhood spaces use today.

Questions for Your Reflection:

How do you see your role in the with children as compared to a classical Montessori guide?

How are materials used in your program?

What types of materials are available for children in your program?

What role do the children take in the maintenance and preparation of their environment?

When and how do you use explicit instruction to guide children? When and how do they have the opportunity to self-correct or use self-correcting materials?

Early Childhood Education can have a lot of buzzwords and misunderstandings. This “Philosophy Spotlight” series intends to introduce you to the origins of a number of currently used philosophies directly from the writings of their founders and accomplished practitioners, as well as modern practices and ideas associated with these philosophies. Note that many of the philosophies and philosophers we reference in the US are Euro-centric in origin. I will do my best to integrate philosophies of development and learning from a more diverse body of knowledge, for the benefit of all children and providers. You’ll notice a significant amount of overlap between philosophies, as well as some stark differences. Use these articles to consider your own approach to early education, and maybe refine how you see you work and design your program. These are intended to be broad overviews; please see the references if you’d like to learn more about each one!

Modern Regulating Bodies/Standards:

Association of Waldorf Schools of North America offers accreditation for Waldorf schools through High School, and WECAN (Waldorf Early Childhood Assocation of North America) offers membership and allows participating organizations, including Family Child Care Homes, to use the term Waldorf.

Origins, Theories and Theorists:

The first Waldorf school was built in the Waldorf Astoria cigarette factory in Stuttgart, Germany in 1919. The factory owner asked Rudolf Steiner to start a school for his employees’ children after Steiner gave a speech there about social renewal in the wake of World War I. Steiner’s school

Steiner created Anthroposophy, a spiritual belief that aligns with Christianity but is not explicitly Christian. Waldorf schools are still influenced by anthroposophy, but the majority would not consider themselves religious.

“We must delay as long as possible the giving of mental concepts in purely intellectual form…man should fully awaken later in life, but the child must be allowed to remain as long as possible in the peaceful, dreamlike state of pictorial imagination of the early years. For if we allow the organism to grow strong in this way, he will develop in later life the intellectuality needed in the world today.” Rudolf Steiner, 1923

The Waldorf philosophy comes with a specific view of child development, spaced out in three phases of seven years each. Early childhood is thought of as the first seven years of life, and is a time for children to engage with physical materials and explore the world as well as their imagination. It is considered too early for intellectual or academic work.

Values:

Creativity and fantasy– Steiner believed that young children live in a fantasy world, and thus should hear stories that continue to encourage their imagination, so as to develop their intuition. He also believed that fairy tales and other fantastical stories are internalized by children as allegories and accessed later as part of their subconscious spiritual and moral development.

Being outdoors and spending time in nature, observing the changes of the seasons and passing of time through ritual.

Limiting early academics. Children in Waldorf schools do not partake in any formal literacy instruction until first grade, and it is believed that academic expectations are a hindrance to a young child’s development.

Little to no use of electronics/technology, including recorded music, at least until upper grades (mostly high school).

Steiner believed that “the human being is a music being,” and placed great importance on children and adults alike creating music.

“Educating the head, the heart, and the hands” was how Steiner phrased his idea for holistic education. This could also be phrased as thinking, feeling, and doing, and represents educating the whole person. Young children in particular are primarily “hands”– they learn through doing, and active physical exploration.

Great emphasis on creative expression; Waldorf schools incorporate arts and music throughout the curriculum.

What You Might Observe in a Waldorf Early Childhood Program:

Practical life activities similar to Montessori; children are encouraged to help cook and serve food, as is developmentally appropriate.

A lot of art and music. Waldorf teachers and children sing together every day as part of their curriculum, and painting and drawing are valued highly, as are crafts such as felting and knitting, even for young children.

Puppets! Puppet Plays are a significant tradition in Waldorf education, intended to teach children the value of storytelling in different ways. These puppets are often very simple and frequently handmade from knotted cloths or felted wool.

Nature tables: low tables with sticks, leaves, stones, flowers, and other items brought inside from the natural world. The children seek out these objects as symbols of seasonal change; dry brown leaves in the fall are replaced with empty shed twigs in the winter, and then fresh green leaves in the spring.

Influence on Modern ECE Programs:

Many modern early childhood programs place a strong emphasis on story telling with young children. An increasing number are bringing in natural artifacts in a way similar to a nature table.

Questions for Your Reflection:

What in your practice might align with Waldorf values?

How does your view of child development agree or disagree with Steiner?

What ideas in Steiner’s statements or in Waldorf schools as they are today challenge or align with beliefs you hold about young children?

A large part of running a care and education program is having a curriculum, but what exactly is a curriculum? This Town square-created resource dives deep into exploring the foundation of a curriculum and guides you in reflecting on your current practice.

What is Curriculum?

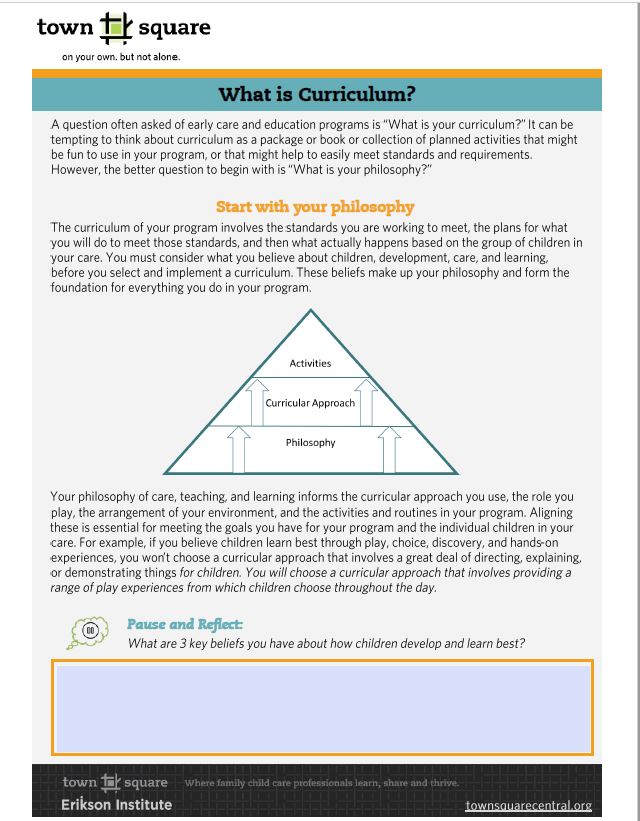

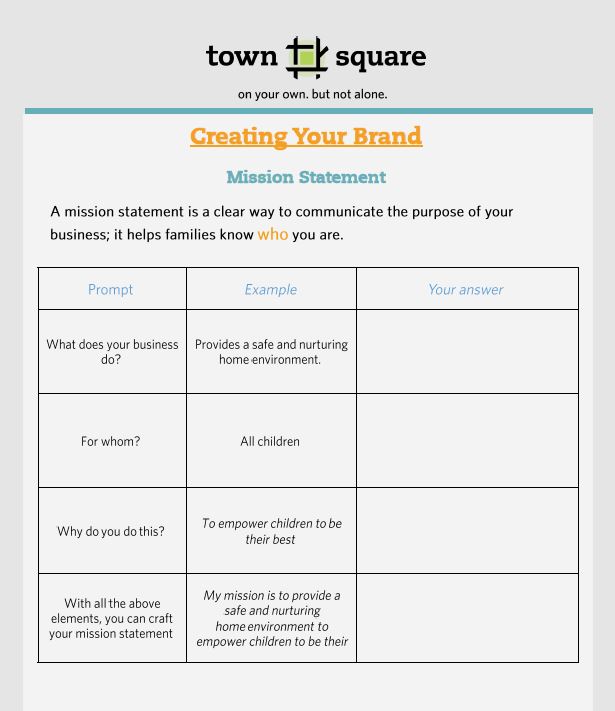

Having a mission and philosophy statement is an essential part of any business; it sets the foundation for how you want to operate and why. Having a written statement can help in centering your business and effectively communicating with families. Use this Town Square-created resource to guide you in developing a mission and philosophy statement.

Mission and Philosophy Resource

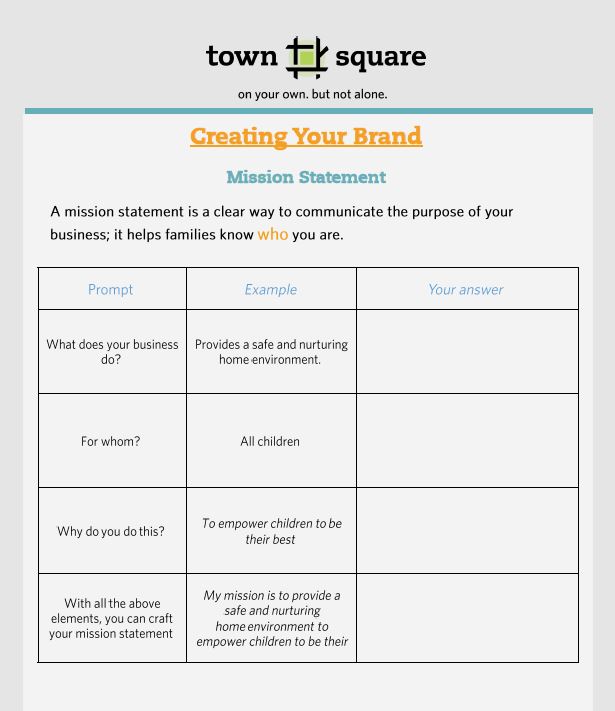

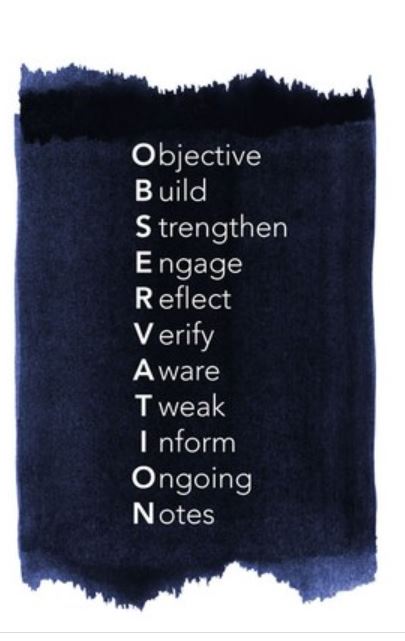

Why Observe Children?

Commonly heard responses are that early care and education (ECE) professionals observe children to monitor progress, to complete required assessments and screenings, and to identify learning or behavior challenges.

Observation is a core piece of the assessment process and continuous quality improvement (CQI) planning. ECE professionals use observation to document a child’s learning and to inform teaching practices. But another reason for observation is to spark learning and development.

Interactions come first

Research shows that young children’s learning occurs best within relationships and with rich interactions. Children need stimulating and focused interactions to learn. Researchers find that boosting children’s thinking skills through quality interactions is critical to children’s learning.

“Children benefit most when teachers engage in stimulating interactions that support learning and are emotionally supportive. Interactions that help children acquire new knowledge and skills provide input to children, elicit verbal responses and reactions from them, and foster engagement in and enjoyment of learning.” (Yoshikawa et al. 2013)

Quality interactions happen when a teacher intentionally plans and carefully thinks about how she approaches and responds to children. Emotionally supportive interactions help children develop a strong sense of well-being and security. Responsive interactions are responses and communication with children that meet their needs in the moment.

Most interactions with children offer ECE professionals the opportunity to engage, interact, instruct, and exchange information that supports healthy development and learning. Relationships between children and teachers grow stronger during everyday interactions. As children gain new information and ideas, ECE professionals can encourage them to share what they think and learn. Deeper thinking and learning engage children in the joy of learning and help to prepare children for new experiences and challenges.

Observation nurtures relationships and learning

Observation helps ECE professionals look at their interactions with children, and discover how important interactions are as they get to know and support children. Observation is a way to connect with children, to discover their connections to others and to their environment. Children who feel cared for, safe, and secure interact with others and engage in their world to learn. They are more likely to gain skills, and to do better as they enter school.

Use observation for an objective view of a child. When you really see the child, you get to know her and see more of her abilities, interests, and personal characteristics. Knowing each child helps you to plan individualized and developmentally informed activities. Look at what the child does and says without evaluating or labeling.

Find ways to build each child’s self-confidence. Reinforce success and effort. He may not be successful in all things but he can learn from failure as well as success. Encourage persistence, curiosity, taking on challenges, and trying new things.

Strengthen relationships as you learn more about the child. Talk to her about what she likes, and discuss shared interests to connect with her. Take her moods and approaches to situations into consideration, and let her know that you understand her perspective.

Observe to engage a child with you, other children, and the learning environment. Set up the environment with activities and materials that appeal to him, address his individual needs, and support his development.

Reflect on observations to assess each child’s progress, understand her needs and personality, improve teaching practices, and plan curriculum. Put ideas into practice to enhance learning and relationships.

Verify questions and concerns about a child. Talk to families and staff about him. Follow up if development or behavior is not typical.

Be aware of the quality of interactions with each child. Step back and consider how and why you and other staff interact with her. Do all interactions nurture relationships and learning?

Make tweaks, or small changes, while observing and afterwards. If something doesn’t work, try another approach or activity instead of “pushing through” with plans. Reflect on why something didn’t work, brainstorm ways to improve activities, and think of new activities to try.

Use information from observations to inform program practices and policies. Take a broad look at how the program supports all children and learning. Use the information for CQI plans.

Make observation an ongoing practice, a part of all interactions and activities, and watch for small changes and individual traits. Ongoing observation offers a chance to be proactive, to prevent problems.

Take notes, either during activities or shortly afterwards. It is easy to forget the quick “aha” moments when you are busy with teaching and care tasks, not to mention all the unplanned interruptions that pop up! Notes also make it easier to identify patterns and growth.

Interaction, relationships, and connections offer the deepest support to learning. Observation connects many pieces of information to give ECE professionals a better picture of each child. Observation is an ongoing, integral part of a quality ECE program, and professionals play an important part.

PDF Version