It’s likely that you have already or will someday work with a family whose children are learning more than one language. There are a number of approaches that families may take to achieve this, including implementing only one language at home and another in the community, or using the One Parent, One Language approach which is just what it sounds like: one parent speaks one language to the child(ren), while the other speaks a different language.

Why do multi language learners benefit from an approach that supports all of their languages?

Not too long ago, the prevailing belief was that children should learn English as soon as possible and focus only on English. Many people thought that learning more than one language was confusing and would lead to language impairments. Now we know that children who learn more than one language are not at any higher risk of speech or language issues, and when assessed appropriately tend to have larger total vocabularies than monolingual children. One way to support multi language learners is simply to make sure their families know how beneficial it is to keep their home language!

There are also significant social-emotional benefits to uplifting a child’s home language. Even very young children can learn early on to “hide” a part of their identity when they don’t feel a social approval for it, such as by no longer speaking in their home language, even with family. When a child feels that their home language is valued, it helps to maintain a sense of pride and “being seen” that supports children’s identities as learners, members of the national culture, and members of their home culture.

How can educators support children’s development in a language they don’t know?

To support children’s multicultural identities, sharing bilingual books, or books that feature some words in a child’s home language, are a great way to demonstrate support for the many ways we have to communicate and introduce all children to the language. Some children might want to be the expert in their home language and have the chance to correct a provider or peer’s pronunciation, and some may not want the attention that brings. Even if you can’t find books with vocabulary that isn’t in English, you may find fairy tales or stories that incorporate cultural features that are familiar to those children. Partner with families for suggestions or ask your local children’s librarian to help you locate appropriate materials.

What are some practical tips for working with children and families when there is a language barrier?

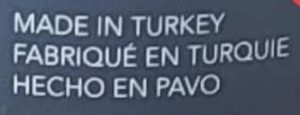

When a family doesn’t speak English, and a provider doesn’t speak the family’s home language, there are some tools to build relationships. While they aren’t perfect, there are many technological ways to facilitate communication across languages. The free Google Translate phone app offers the ability to translate conversations in real time across dozens of languages, with the option to write and translate if spoken word isn’t supported in the language you need. The website can also translate newsletters or other written communication. Just be aware that computers make mistakes that real people do not, like this label on a beauty product that was made in Turkey, the country– except, in Spanish, it appears that it was made in a turkey, the bird!

Image via Steve the vagabond and silly linguist 🇿🇦 on X: “Made in a turkey https://t.co/uAGet2vMKg” / X

Image via Steve the vagabond and silly linguist 🇿🇦 on X: “Made in a turkey https://t.co/uAGet2vMKg” / X

Learning some words in the child’s home language is important– particularly words relating to their needs, like “hungry,” “tired,” and “toilet” or “diaper.” Making yourself a phonetic “cheat sheet” can help. For example, if a child who speaks Japanese joins your group, you could write:

Hungry= on-ah-ka-ga-su-ita

Tired= tska-re-ta

Toilet= ben-jo

Diaper= Oh-muh-tsu

If possible, ask the family to teach the proper vocabulary and pronunciation– it’s possible the family uses a local accent or dialect that’s different than what a translator uses as standard.

How can educators support peer relationships across languages?

There are many kinds of play that don’t require a lot of language at first! Offering art and sensory experiences with enough materials to share will naturally lead to children demonstrating their discoveries to each other. Large motor play, like obstacle courses, will be easy for children to model for each other.

Educators can actively encourage children to include each other by inviting the new child into activities or asking one child to be the new child’s “partner” and show them around.

Remember to model empathy for the new child. Entering a new environment can be frightening for many children, and not understanding the language adds an additional dimension to contend with. Talking with the children in advance about how to help their new friend feel more comfortable might lead to some great ideas that wouldn’t be obvious for adults. This can also enhance peer relationships to offer children the opportunity to learn what is comforting for each member of the group.

Questions for Reflection:

- Which of these strategies seems like it would be the easiest to incorporate into your program?

- What other ideas do you have to support multi language learners and their families?